- 1. Microservices for Java Developers

- 2. Spring Boot for Microservices

- 3. Eclipse MicroProfile for Microservices

- 4. API Gateway with Apache Camel

- 5. Deploying Microservices at Scale with Docker and Kubernetes

- 6. Hands-on Cluster Management, Failover, and Load Balancing

- 7. Distributed Tracing with OpenTracing

- 8. Where Do We Go from Here?

Microservices for Java Developers

Second Edition

A Hands-on Introduction to Frameworks and Containers

Microservices for Java Developers

Copyright © 2019 Red Hat, Inc. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc. , 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles ( http://oreilly.com ). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com .

- Acquisitions Editor: Mary Treseler

- Developmental Editors: Chris Guzikowski and Eleanor Bru

- Production Editor: Nan Barber

- Copyeditor: Rachel Head

- Proofreader: Nan Barber

- Interior Designer: David Futato

- Cover Designer: Karen Montgomery

- Illustrator: Rebecca Demarest

- April 2019: Second Edition

Revision History for the Second Edition

- 2019-03-28: First Release

- 2019-06-17: Second Release

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Microservices for Java Developers , the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

The views expressed in this work are those of the authors, and do not represent the publisher’s views. While the publisher and the authors have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the authors disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

This work is part of a collaboration between O’Reilly and Red Hat. See our statement of editorial independence .

978-1-492-03828-3

[LSI]

Chapter 1. Microservices for Java Developers

What Can You Expect from This Report?

This report is for Java developers and architects interested in developing microservices. We start the report with a high-level introduction and take a look at the fundamental prerequisites that should be in place to be successful with a microservices architecture. Unfortunately, just using new technology doesn’t magically solve distributed systems problems. Therefore, in this chapter we also explore some of the forces involved and what successful companies have done to make microservices work for them, including aspects such as culture, organizational structure, and market pressures. Then we take a deep dive into a few Java frameworks for implementing microservices. The accompanying source code repository can be found on GitHub . Once we have our hands dirty, we’ll come back up for air and discuss issues around deployment, clustering, and failover, and how Docker and Kubernetes deliver solutions in these areas. Then we’ll get back into the details with some hands-on examples with Docker, Kubernetes, and OpenShift to demonstrate the power they bring to cloud-native microservices architectures. The last chapter offers some thoughts on topics that we cannot cover in this report but that are nonetheless important, like configuration, logging, and continuous delivery.

Transitioning to microservices involves more than just a technological change. Implementations of microservices have roots in complex adaptive theory, service design, technology evolution, domain-driven design, dependency thinking, promise theory, and other areas. They all come together to allow the people in an organization to truly exhibit agile, responsive learning behaviors and to stay competitive in a fast-evolving business world. Let’s take a closer look.

You Work for a Software Company

Software really is eating the world. Businesses are slowly starting to realize this, and there are two main drivers for this phenomenon: delivering value through high-quality services and the rapid commoditization of technology. This report is primarily written in a hands-on, by-example format. But before we dive into the technology, we need to properly set the stage and understand the forces at play. We have been talking ad nauseam in recent years about making businesses agile , but we need to fully understand what that means. Otherwise it’s just a nice platitude that everyone glosses over.

The Value of Service

For more than 100 years, our business markets have been about creating products and driving consumers to want those products: desks, microwaves, cars, shoes, whatever. The idea behind this “producer-led” economy comes from Henry Ford’s theory that if one could produce great volumes of a product at low cost, the market would be virtually unlimited. For that to work, you also need a few one-way channels to directly market to the masses to convince them that they need these products and their lives will be substantially better with them. For most of the 20th century, these one-way channels existed in the form of advertisements on TV, in newspapers and magazines, and on highway billboards. However, this producer-led economy has been flipped on its head because markets are fully saturated with products (how many phones/cars/TVs do you need?). Further, the internet, along with social networks, is changing the dynamics of how companies interact with consumers (or more importantly, how consumers interact with them).

Social networks allow us, as consumers, to more freely share information with one another and the companies with which we do business. We trust our friends, family, and others more than we trust marketing departments. That’s why we go to social media outlets to choose restaurants, hotels, and airlines. Our positive feedback in the form of reviews, tweets, shares, and the like can positively favor the brand of a company, and our negative feedback can just as easily and very swiftly destroy a brand. As depicted in Figure 1-1 , there is now a powerful bidirectional flow of information between companies and their consumers that previously never existed, and businesses are struggling to keep up with the impact of not owning their brands.

Postindustrial companies are learning they must nurture their relationships (using bidirectional communication) with customers to understand how to bring value to them. Companies do this by providing ongoing conversation through service, customer experience, and feedback. Customers choose which services to consume and which to pay for depending on which ones bring them value and good experiences. Take Uber, for example, which doesn’t own any inventory or sell products per se. You don’t get any value out of sitting in someone else’s car, but you may be trying to get somewhere that does bring value (a business meeting, for example). In this way, using Uber’s service creates value. Going forward, companies will need to focus on bringing valuable services to customers, and technology will drive this through digital services.

The Commoditization of Technology

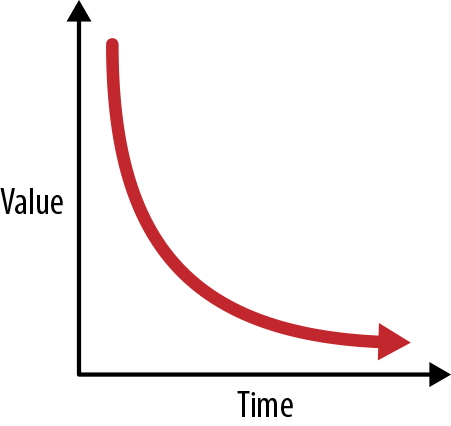

Technology follows a similar boom-and-bust cycle as economics, biology, and law. It has led to great innovations, like the steam engine, the telephone, and the computer. In our competitive markets, however, game-changing innovations require a lot of investment and build-out to quickly capitalize. This brings more competition, greater capacity, and falling prices, eventually making the once-innovative technology a commodity. Upon these commodities we continue to innovate and differentiate, and the cycle continues. This commoditization has brought us from the mainframe to the personal computer to what we now call “cloud computing,” which is a service bringing us commodity computing with almost no upfront capital expenditure. On top of cloud computing, we’re now seeing new innovation in the form of digital services. Figure 1-2 shows the value over time curve.

Figure 1-2. The value over time curve

Open source is also leading the charge in the technology space. Following the commoditization curve, open source is a place developers can go to challenge proprietary vendors by building and innovating on software that was once only available (without source, no less) with high license costs. This drives communities to build things like operating systems (Linux), programming languages (Go), message queues (Apache ActiveMQ), and web servers ( httpd ). Even companies that originally rejected open source are starting to come around by open sourcing their technologies and contributing to existing communities. As open source and open ecosystems have become the norm, we’re starting to see a lot of the innovation in software technology coming directly from open source communities (e.g., Apache Spark, Docker, and Kubernetes).

Disruption

The confluence of these two factors—service design and technology evolution—is lowering the barrier of entry for anyone with a good idea to start experimenting and trying to build new services. You can learn to program, use advanced frameworks, and leverage on-demand computing for next to nothing. You can post to social networks, blog, and carry out bidirectional conversations with potential users of your service for free. With the fluidity of our business markets, any over-the-weekend startup can put a legacy company out of business.

And this fact scares most CIOs and CEOs. As software quickly becomes the mechanism by which companies build digital services and experiences and differentiate themselves, many are realizing that they must become software companies in their respective verticals. Gone are the days of massive outsourcing and treating IT as a commodity or cost center. For companies to stay truly competitive, they must embrace software as a differentiator, and to do that, they must embrace organizational agility.

Embracing Organizational Agility

Companies in the industrial-era thinking of the 20th century are not built for agility. They are built to maximize efficiencies, reduce variability in processes, and eliminate creative thinking in workers, placing them into boxes the way you would organize an assembly line. They are built like machines to take inputs, apply a highly tuned process, and create outputs. They are structured with top-down hierarchical management to facilitate this machine-like thinking. Changing the machine requires 18-month planning cycles. Information from the edges goes through many layers of management and translation to get to the top, where decisions are made and handed back down. This organizational approach works great when creating products and trying to squeeze every bit of efficiency out of a process, but does not work for delivering services. Figure 1-3 illustrates the relation between efficiency and flexibility.

Figure 1-3. Relation between efficiency and flexibility

Customers don’t fit in neat boxes or processes. They show up whenever they want. They want to talk to a customer service representative, not an automated phone system. They ask for things that aren’t on the menu. They need to input something that isn’t on the form. Customers want convenience. They want a conversation. And they get mad if they have to wait.

This means our customer-facing services need to account for variability. They need to be able to react to the unexpected. This is at odds with efficiency. Customers want to have a conversation through a service you provide them, and if that service isn’t sufficient for solving their needs, you need loud, fast feedback about what would help solve their needs and what’s getting in their way. This feedback can be used by the maintainers of the service to quickly adjust the service and interaction models to better suit users. You cannot wait for decisions to bubble up to the top and go through lengthy planning cycles; you need to make decisions quickly with the information you have at the edges of your business. You need autonomous, purpose-driven, self-organizing teams that are responsible for delivering a compelling experience to consumers (paying customers, business partners, peer teams, etc.). Rapid feedback cycles, autonomous teams, shared purpose, and conversation are the prerequisites that organizations must embrace to be able to navigate and live in a postindustrial, unknown, uncharted world of business disruption.

No book on microservices would be complete without quoting Conway’s law: “Organizations which design systems…are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations.”

To build agile software systems, we must start with building agile organizational structures. This structure will facilitate the prerequisites we need for microservices, but what technology do we use? Building distributed systems is hard, and in the subsequent sections, we’ll take a look at the problems you must keep in mind when building and designing these services.

What Is a Microservices Architecture?

A microservices architecture (MSA) is an approach to building software systems that decomposes business domain models into smaller, consistently bounded contexts implemented by services. These services are isolated and autonomous yet communicate to provide some piece of business functionality. Microservices are typically implemented and operated by small teams with enough autonomy that each team and service can change the details of its internal implementation (including replacing it outright!) with minimal impact across the rest of the system. Figure 1-4 illustrates how having independent teams aids agility.

Figure 1-4. Independent teams aid agility

Teams communicate through promises , which are a way a service can publish intentions to other components or systems that may wish to use the service. They specify these promises with interfaces of their services and via wikis that document their services. If there isn’t enough documentation, or the API isn’t clear enough, the service provider hasn’t done their job. (There’ll be a little more on promises and promise theory in the next section.)

Each team is responsible for designing its service, picking the right technology for the problem set, deploying and managing the service, and waking up at 2 a.m. to deal with any issues. For example, at Amazon, there is a single team that owns the tax calculation functionality that gets called during checkout. The models within this service (item, address, tax, etc.) are all understood to mean “within the context of calculating taxes” for a checkout; there is no confusion about these objects (e.g., is the item a return item or a checkout item?). The team that owns the tax calculation service designs, develops, and operates this service. Amazon has the luxury of a mature set of self-service tools to automate a lot of the build/deploy/operate steps, but we’ll come back to that.

With microservices, we can scope the boundaries of a service, which helps us:

-

Understand what the service is doing without getting tangled up in other concerns in a larger application.

-

Quickly build the service locally.

-

Pick the right technology for the problem (lots of writes? lots of queries? low latency? bursty?).

-

Test the service.

-

Build/deploy/release at the cadence necessary for the business, which may be independent of that of other services.

-

Identify and horizontally scale parts of the architecture where needed.

-

Improve the resiliency of the system as a whole.

MSA helps solve the problem of how we decouple our services and teams to move quickly at scale. It allows teams to focus on providing the services and making changes when necessary, and to do so without costly synchronization points. Here are some things you won’t hear about once you’ve adopted microservices:

-

Jira tickets

-

Unnecessary meetings

-

Shared libraries

-

Enterprise-wide canonical models

Is a microservices architecture right for you? Microservices have a lot of benefits, but they come with their own set of drawbacks. You can think of microservices as an optimization for problems that require the ability to change things quickly at scale, but with a price. This approach is not efficient. It can be more resource-intensive. You may end up with what looks like duplication. Operational complexity is a lot higher. It becomes very difficult to understand the system holistically. It becomes significantly harder to debug problems. In some areas you may have to relax the notion of a transaction. Teams may not have been designed to work like this.

Not every part of the business has to be able to change on a dime. A lot of customer-facing applications do. Backend systems may not. But as those two worlds start to blend together, we may see the forces that justify microservices architectures push to other parts of the system.

Challenges

Designing cloud-native applications following a microservices approach requires thinking differently about how to build, deploy, and operate them. We can’t simply build our application thinking we know all the ways it will fail and then just prevent those. In complex systems like those built with microservices, we must be able to deal with uncertainty. This section will identify five main things to keep in mind when developing microservices.

Design for Faults

In complex systems, things fail. Hard drives crash, network cables get unplugged, we do maintenance on the live database instead of the backups, and virtual machines (VMs) disappear. Single faults can be propagated to other parts of the system and result in cascading failures that take an entire system down.

Traditionally, when building applications, we’ve tried to predict what pieces of our app (e.g., n -tier) might fail and build up a wall big enough to keep them from failing. This mindset is problematic at scale because we cannot always predict what things can go wrong in complex systems. Things will fail, so we must develop our applications to be resilient and handle failure, not just prevent it. We should be able to deal with faults gracefully and not let faults propagate to total failure of the system.

Building distributed systems is different from building shared-memory, single-process, monolithic applications. One glaring difference is that communication over a network is not the same as a local call with shared memory. Networks are inherently unreliable. Calls over the network can fail for any number of reasons (e.g., signal strength, bad cables/routers/switches, and firewalls), and this can be a major source of bottlenecks. Not only does network unreliability have performance implications with regard to response times to clients of your service, but it can also contribute to upstream systems failure.

Latent network calls can be very difficult to debug; ideally, if your network calls cannot complete successfully, they fail immediately, and your application notices quickly (e.g., through

IOException

). In this case, you can

quickly take corrective action, provide degraded functionality, or just

respond with a message stating the request could not be completed

properly and that users should try again later. But errors in network requests or

distributed applications aren’t always that easy. What if the downstream

application you must call takes longer than normal to respond? This is

a killer because now your application must take into account this slowness

by throttling requests, timing out downstream requests, and potentially

stalling all calls through your service. This backup can cause upstream

services to experience slowdowns and even grind to a halt. And it can cause

cascading failures.

Design with Dependencies in Mind

To be able to move fast and be agile from an organizational or distributed systems standpoint, we have to design systems with dependency thinking in mind; we need loose coupling in our teams, our technology, and our governance. One of the goals with microservices is to take advantage of autonomous teams and autonomous services. This means being able to change things as quickly as the business needs without impacting the services around us or the system at large. It also means we should be able to depend on services, but if they’re not available or are degraded, we need to be able to handle this gracefully.

In his book Dependency-Oriented Thinking (InfoQ Enterprise Software Development Series), Ganesh Prasad hits it on the head when he says, “One of the principles of creativity is to drop a constraint . In other words, you can come up with creative solutions to problems if you mentally eliminate one or more dependencies.” The problem is that our organizations were built with efficiency in mind, and that brings along a lot of tangled dependencies.

For example, when you need to consult with three other teams to make a change to your service (DBA, QA, and security), this is not very agile; each one of these synchronization points can cause delays. It’s a brittle process. If you can shed those dependencies or build them into your team (you definitely can’t sacrifice safety or security, so you should build those components into your team), you’re free to be creative and more quickly solve problems that customers face or that the business foresees without costly people bottlenecks.

Another angle to the dependency management story is what to do with legacy systems. Exposing the details of backend legacy systems (COBOL copybook structures, XML serialization formats used by a specific system, etc.) to downstream systems is a recipe for disaster. Making one small change (customer ID is now 20 numeric characters instead of 16) now ripples across the system and invalidates assumptions made by those downstream systems, potentially breaking them. We need to think carefully about how to insulate the rest of the system from these types of dependencies.

Design with the Domain in Mind

Models have been used for centuries to simplify and understand a problem through a certain lens. For example, the GPS maps on our phones are great models for navigating a city while walking or driving, but this model would be completely useless to someone flying a commercial airplane. The models pilots use are more appropriate to describe waypoints, landmarks, and jet streams. Different models make more or less sense depending on the context from which they’re viewed. Eric Evans’s seminal book Domain-Driven Design (Addison-Wesley) helps us build models for complex business processes that can also be implemented in software. Ultimately the real complexity in software is not the technology but rather the ambiguous, circular, contradicting models that business folks sort out in their heads on the fly. Humans can understand models given some context, but computers need a little more help; these models and the context must be baked into the software. If we can achieve a level of modeling that is bound to the implementation (and vice versa), anytime the business changes, we can more clearly understand how that changes the software. The process we embark upon to build these models and the development of the language surrounding them takes time and requires fast feedback loops.

One of the tools Evans presents is identifying and explicitly separating the different models and ensuring they are each cohesive and unambiguous within their own bounded context ( Figure 1-5 ). Context mapping lets us visualize the relationships between those different contexts.

Figure 1-5. Bounded contexts

A bounded context is a set of domain objects that implement a model that

tries to simplify and communicate a part of the business, code, and

organization. Often, we strive for efficiency when designing our

systems when we really need flexibility (sound familiar?). In a simple

auto parts application, for example, we might try to come up with a unified “canonical model”

of the entire domain, and end up with objects like

Part

,

Price

,

and

Address

. If the inventory application used the

Part

object it

would be referring to a type of part, like a type of brake or wheel.

In an automotive quality assurance system,

Part

might refer to a very

specific part with a serial number and unique identifier to track

certain quality test results and so forth. We might try diligently to

efficiently reuse the same canonical model, but inventory

tracking and quality assurance are different business concerns that use

the

Part

object semantically differently. With a bounded context for the inventory system, a

Part

would explicitly be modeled as

PartType

and be understood

within that context to represent a “type of part,” not a specific

instance of a part. With two separate bounded contexts, these

Part

objects can evolve consistently within their own models without

depending on one another in weird ways, and thus we’ve achieved a level of

agility or flexibility. The context map is what allows us to keep track of the different contexts within the application, to prevent ambiguity.

This deep understanding of the domain takes time. It may take a few iterations to fully understand the ambiguities that exist in business models and properly separate them out and allow them to change independently. This is at least one reason starting off building microservices is difficult. Carving up a monolith is no easy task, but a lot of the concepts are already baked into the monolith; your job is to identify and separate them. With a greenfield project, you cannot carve up anything until you deeply understand the domain. In fact, all of the microservice success stories we hear about (like Amazon and Netflix) started out going down the path of the monolith before they successfully made the transition to microservices.

Design with Promises in Mind

In a microservices environment with autonomous teams and services, it’s very important to keep in mind the relationship between service provider and service consumer. As an autonomous service team, you cannot place obligations on other teams and services because you do not own them; they’re autonomous by definition. All you can do is choose whether or not to accept their promises of functionality or behavior. As a provider of a service to others, all you can do is promise them a certain behavior. They are free to trust you or not. Promise theory, a model first proposed by Mark Burgess in 2004 and covered in his book In Search of Certainty (O’Reilly), is a study of autonomous systems including people, computers, and organizations providing services to each other. Figure 1-6 illustrates the difference between an obligation and a promise: an obligation is placed on a team, while a promise is made by the team.

Figure 1-6. Obligation versus promise

In terms of distributed systems, promises help articulate what a service may provide and make clear what assumptions can and cannot be made. For example, suppose our team owns a book recommendation service, and we promise a personalized set of book recommendations for a specific user you ask about. What happens when you call our service, and one of our backends (the database that stores that user’s current view of recommendations) is unavailable? We could throw exceptions and stack traces back to you, but that would not be a very good experience and could potentially blow up other parts of the system. Because we made a promise, we can instead try to do everything we can to keep it, including returning a default list of books, or a subset of all the books. There are times when promises cannot be kept, and identifying the best course of action in these circumstances should be driven by the desired experience or outcome for our users. The key here is the onus on our service to try to keep its promise (return some recommendations), even if our dependent services cannot keep theirs (the database was down). In the course of trying to keep a promise, it helps to have empathy for the rest of the system and the service quality we’re trying to uphold.

Another way to look at a promise is as an agreed-upon exchange that provides value for both parties (like a producer and a consumer). But how do we go about deciding between two parties what is valuable and what promises we’d like to agree upon? If nobody calls our service or gets value from our promises, how useful is the service? One way of articulating the promises between consumers and providers is with consumer-driven contracts . With consumer-driven contracts, we are able to capture the value of our promises with code or assertions, and as a provider, we can use this knowledge to test whether we’re upholding our promises.

Distributed Systems Management

At the end of the day, managing a single system is easier than for a distributed one. If there’s just one machine, and one application server, and there are problems with the system, we know where to look. If we need to make a configuration change, upgrade to a specific version, or secure it, it’s all in one physical and logical location. Managing, debugging, and changing it is easier. A single system may work for some use cases, but for ones where scale is required, we may look to leverage microservices. As we discussed earlier, however, microservices are not free; the trade-off for having flexibility and scalability is having to manage a complicated system.

When it comes to managing a microservices deployment, here are some questions to consider:

-

How do we start and stop a fleet of services?

-

How do we aggregate logs/metrics/service level agreements (SLAs) across microservices?

-

How do we discover services in an elastic environment where they can be coming, going, moving, etc.?

-

How do we do load balancing?

-

How do we learn about the health of our cluster or individual services?

-

How do we restart services that have failed?

-

How do we do fine-grained API routing?

-

How do we secure our services?

-

How do we throttle or disconnect parts of a cluster if it starts to crash or act unexpectedly?

-

How do we deploy multiple versions of a service and route to them appropriately?

-

How do we make configuration changes across a large fleet of services?

-

How do we make changes to our application code and configuration in a safe, auditable, repeatable manner?

These are not easy problems to solve. The rest of this report will be devoted to getting Java developers up and running with microservices and able to solve some of the problems listed here.

Technology Solutions

Throughout the rest of the report, we’ll introduce you to some popular technology components and how they help solve some of the problems of developing and delivering software using a microservices architecture. As touched upon earlier, microservices aren’t just a technological problem, and getting the right organizational structure and teams in place to facilitate this approach is paramount. Switching from SOAP to REST doesn’t make a microservices architecture.

The first step for a Java development team creating microservices is to get something working locally on their machines. This report will introduce you to three opinionated Java frameworks for working with microservices: Spring Boot, MicroProfile, and Apache Camel. Each framework has upsides for different teams, organizations, and approaches to microservices. As is the norm with technology, some tools are a better fit for the job or team using them than others. Of course, these are not the only frameworks to use. There are a couple that take a reactive approach to microservices, like Vert.x and Lagom . The mindshift for developing with an event-based model is a bit different and requires a different learning curve, though, so for this report we’ll stick with a model that most enterprise Java developers will find comfortable.

If you want to know more about reactive programming and reactive microservices, you can download the free ebook Building Reactive Microservices in Java by Clement Escoffier from the Red Hat Developers website.

The goal of this report is to get you up and running with the basics for each framework. We’ll dive into a few advanced concepts in the last chapter, but for the first steps with each framework, we’ll assume a “Hello World” microservice application. This report is not an all-encompassing reference for developing microservices; each chapter ends with links to reference material that you can explore to learn more as needed. We will iterate on the Hello World application by creating multiple services and show some simple interaction patterns.

The final iteration for each framework will look at concepts like bulkheading and promise theory to make services resilient in the face of faults. We will dig into parts of the NetflixOSS stack, like Hystrix, that can make our lives easier when implementing this functionality. We will discuss the pros and cons of this approach and explore what other options exist.

First, though, let’s take a look at the prerequisites you’ll need to get started.

Preparing Your Environment

We will be using Java 1.8 for the examples in this report and building them with Maven. Please make sure for your environment you have the following prerequisites installed:

-

JDK 1.8

-

Maven 3.5+

-

Access to a command-line shell (bash, PowerShell, cmd, Cygwin, etc.)

The Spring ecosystem has some great tools you may wish to use either at the command line or in an IDE. Most of the examples will stick to the command line to stay IDE-neutral and because each IDE has its own way of working with projects. For Spring Boot, we’ll use the Spring Boot CLI 2.1.x .

Alternative IDEs and tooling for Spring, MicroProfile and Camel include:

Finally, when you build and deploy your microservices as Docker containers running inside of Kubernetes, you’ll want the following tools to bootstrap a container environment on your machines:

Chapter 2. Spring Boot for Microservices

Spring Boot is an opinionated Java framework for building microservices based on the Spring dependency injection framework. Spring Boot facilitates creation of microservices through reduced boilerplate, configuration, and developer friction. This is a similar approach to the two other frameworks we’ll look at.

Advantages of Spring Boot

Spring Boot offers the following advantages in comparison to the Spring framework:

-

Favoring automatic, conventional configuration by default

-

Curating sets of popular starter dependencies for easier consumption

-

Simplifying application packaging

-

Baking in application insight (e.g., metrics and environment info)

Simplified Configuration

Spring historically was a nightmare to configure. Although the framework

improved upon other high-ceremony component models (EJB 1.x, 2.x, etc.),

it did come along with its own set of heavyweight usage patterns.

Namely, Spring required a lot of XML configuration and a deep

understanding of the individual beans needed to construct

JdbcTemplates

,

JmsTemplates

,

BeanFactory

lifecycle hooks, servlet listeners, and many

other components. In fact, writing a simple “Hello World” with Spring MVC required understanding of DispatcherServlet and a whole host of

Model–View–Controller classes. Spring Boot aims to eliminate all of this

boilerplate configuration with some implied conventions and simplified

annotations—although, you can still finely tune the underlying beans

if you need to.

Starter Dependencies

Spring was used in large enterprise applications that typically leveraged lots of different technologies to do the heavy lifting: JDBC databases, message queues, file systems, application-level caching, etc. Developers often had to stop what they were doing, switch cognitive contexts, figure out what dependencies belonged to which piece of functionality (“Oh, I need the JPA dependencies!”), and spend lots of time sorting out versioning mismatches and other issues that arose when trying to use these various pieces together. Spring Boot offers a large collection of curated sets of libraries for adding these pieces of functionality. These starter modules allow you to add things like:

-

Java Persistence API (JPA)

-

NoSQL databases like MongoDB, Cassandra, and Couchbase

-

Redis caching

-

Tomcat/Jetty/Undertow servlet engines

-

Java Transaction API (JTA)

Adding a submodule to an application brings in a curated set of transitive dependencies and versions that are known to work together, saving developers from having to sort out dependencies themselves.

Application Packaging

Spring Boot really is a set of bootstrap libraries with some convention

for configurations, but there’s no reason why you couldn’t run a Spring

Boot application inside your existing application servers as a Web Application Archive (WAR). The idiom that most developers who use Spring Boot prefer for their applications is the self-contained Java Archive (JAR) packaging, where all dependencies and application code are bundled together with a flat class loader in a single JAR. This makes it easier to understand application startup, dependency ordering, and log statements. More importantly, it also helps reduce the

number of moving pieces required to take an app safely to production.

You don’t take an app and chuck it into an app server; the

app, once it’s built, is ready to run as is—standalone—including

embedding its own servlet container if it uses servlets. That’s right, a

simple

java -jar

<name.jar>

is enough to start your application now!

Spring Boot, MicroProfile/Thorntail, and many other frameworks like Vert.x and Dropwizard all follow this pattern of

packaging everything into an executable uber-AR.

But what about the management things we typically expect out of an application server?

Production-Ready Features

Spring Boot ships with a module called

spring boot actuator

that enables things

like metrics and statistics about your application. For example, you can

collect logs, view metrics, perform thread dumps, show environment

variables, understand garbage collection, and show which beans are configured

in the BeanFactory. You can expose this information via HTTP or Java Management Extensions (JMX), or you can even log in directly to the process via SSH.

With Spring Boot, you can leverage the power of the Spring framework and reduce boilerplate configuration and code to more quickly build powerful, production-ready microservices. Let’s see how.

Getting Started

We’re going to use the Spring Boot command-line interface (CLI) to bootstrap our first Spring Boot application (the CLI uses Spring Initializr under the covers). You are free to explore the different ways to do this if you’re not comfortable with the CLI. Alternatives include using Spring Initializr plug-ins for your favorite IDE, or using the web version . The Spring Boot CLI can be installed a few different ways, including through package managers and by downloading it straight from the website. Check for instructions on installing the CLI most appropriate for your development environment .

Once you’ve installed the CLI tools, you should be able to check the version of Spring you have:

$ spring --version Spring CLI v2.1.1.RELEASE

If you can see a version for your installation of the CLI, congrats! Now navigate to the directory where you want to host your examples from the report and run the following command:

$ spring init --build maven --groupId com.redhat.examples \ --version 1.0 --java-version 1.8 --dependencies web \ --name hello-springboot hello-springboot

After running this command, you should have a directory named hello-springboot with a complete Spring Boot application. If you run the command and end up with a demo.zip , then just unzip it and continue. Let’s take a quick look at what those command-line options are:

-

--build -

The build management tool we want to use.

mavenandgradleare the two valid options at this time. -

--groupId -

The

groupIdto use in our Maven coordinates for our pom.xml . Unfortunately this does not properly extend to the Java package names that get created; these need to be modified by hand. -

--version -

The version of our application. This will be used in later iterations, so set to 1.0.

-

--java-version -

The build compiler version for the JDK.

-

--dependencies -

This is an interesting parameter; we can specify fully baked sets of dependencies for doing common types of development. For example,

webwill set up Spring MVC and embed an internal servlet engine (Tomcat by default, Jetty and Undertow as options). Other convenient dependency bundles/starters includejpa,security, andcassandra).

Now, from the hello-springboot directory, try running the following command:

$ mvn spring-boot:run

If everything boots up without any errors, you should see some logging similar to this:

2018-12-13 13:18:19 ---[main]TomcatWebServer : Tomcat started on port(s):8080(http)with context path''2018-12-13 13:18:19 ---[main]HelloSpringbootApplication : Started HelloSpringbootApplication in 2.3 seconds(JVM runningfor10.265)

Congrats! You have just gotten your first Spring Boot application up and running. If you navigate to http://localhost:8080 in your browser, you should see the output shown in Figure 2-1 .

Figure 2-1. Whitelabel error page

This default error page is expected since our application doesn’t do anything yet. Let’s move on to the next section to add a REST endpoint to put together a Hello World use case.

Hello World

Now that we have a Spring Boot application that can run, let’s add some

simple functionality. We want to expose an HTTP/REST endpoint at

/api/hello

that will return “Hello Spring Boot from

X

" where

X

is the IP

address where the service is running. To do this, navigate to

src/main/java/com/examples/hellospringboot

. This location should have been created for

you if you followed the preceding steps. Then create a new Java class called

HelloRestController

, as shown in

Example 2-1

. We’ll add a method named

hello()

that returns a string along with the IP address of where the service is running. You’ll see in

Chapter 6

, when we discuss load balancing and service discovery, how the host IPs can be used to demonstrate proper failover, load balancing, etc.

Example 2-1. src/main/java/com/examples/hellospringboot/HelloRestController.java

publicclassHelloRestController{publicStringhello(){Stringhostname=null;try{hostname=InetAddress.getLocalHost().getHostAddress();}catch(UnknownHostExceptione){hostname="unknown";}return"Hello Spring Boot from "+hostname;}}

Add the HTTP Endpoints

At this point, this piece of code is just a POJO (plain old Java object), and you could (and should) write a unit test that verifies its behavior. To expose this as a REST endpoint, we’re going to make use of the following annotations in Example 2-2 :

-

@RestController -

Tells Spring this is an HTTP controller capable of exposing HTTP endpoints (GET, PUT, POST, etc.)

-

@RequestMapping -

Maps specific parts of the HTTP URI path to classes, methods, and parameters in the Java code

Note that import statements are omitted.

Example 2-2. src/main/java/com/examples/hellospringboot/HelloRestController.java

@RestController@RequestMapping("/api")publicclassHelloRestController{@RequestMapping(method=RequestMethod.GET,value="/hello",produces="text/plain")publicStringhello(){Stringhostname=null;try{hostname=InetAddress.getLocalHost().getHostAddress();}catch(UnknownHostExceptione){hostname="unknown";}return"Hello Spring Boot from "+hostname;}}

In this code, all we’ve done is add the aforementioned annotations. For

example,

@RequestMapping("/api")

at the class level says “map any

method-level HTTP endpoints under this root URI path.” When we add

@RequestMapping(method = RequestMethod.GET, value = "/hello", produces = "text/plain")

, we are telling Spring to expose an HTTP GET endpoint at

/hello

(which will really be

/api/hello

) and map requests with a media type of

Accept: text/plain

to this method. Spring Boot defaults to using an

embedded Tomcat servlet container, but this can be switched to other

options like Undertow or Jetty.

If you build the application and run

spring-boot:run

again, you should

be able to reach your HTTP endpoint:

$ mvn clean spring-boot:run

Now if you point your browser to http://localhost:8080/api/hello , you should see a response similar to Figure 2-2 .

Figure 2-2. Successful hello

What if we want to add some environment-aware configuration to our application? For example, instead of saying “Hello,” maybe you want to say “Guten Tag” if we deploy our app in production for German users. We need a way to inject properties into our app.

Externalize Configuration

Spring Boot makes it easy to use external property sources like

properties files, command-line arguments, the OS environment, or Java

system properties. We can even bind entire “classes” of properties to

objects in our Spring context. For example, if we want to bind all

helloapp.*

properties to the

HelloRestController

, we can add

@ConfigurationProperties(prefix="helloapp")

, and Spring Boot will

automatically try to bind

helloapp.foo

and

helloapp.bar

to Java Bean

properties in the

HelloRestController

class. We can define new

properties in

src/main/resources/application.properties

. The

application.properties

file was automatically

created for us when we created our project. (Note that we could change the

filename to

application.yml

and Spring would still recognize the

YAML file as the source of properties.)

Let’s add a new property to our src/main/resources/application.properties file:

helloapp.saying=Guten Tag aus

Next we add the

@ConfigurationProperties

annotation and our new

saying

field to the

HelloRestController

class, as shown in

Example 2-3

. Note we also need setters.

Example 2-3. src/main/java/com/examples/hellospringboot/HelloRestController.java

@RestController@RequestMapping("/api")@ConfigurationProperties(prefix="helloapp")publicclassHelloRestController{privateStringsaying;@RequestMapping(method=RequestMethod.GET,value="/hello",produces="text/plain")publicStringhello(){Stringhostname=null;try{hostname=InetAddress.getLocalHost().getHostAddress();}catch(UnknownHostExceptione){hostname="unknown";}returnsaying+" "+hostname;}publicvoidsetSaying(Stringsaying){this.saying=saying;}}

Stop the application from running (if you haven’t already) and restart it:

$ mvn clean spring-boot:run

Now if you navigate to http://localhost:8080/api/hello , you should see the German version of the saying as shown in Figure 2-3 .

Figure 2-3. Successful German greeting

We can now externalize properties that will change depending on the environment in which we are running. Things like service URIs, database URIs and passwords, and message queue configurations would all be great candidates for external configuration. Don’t overdo it, though; not everything needs to change depending on the environment! Ideally an application would be configured exactly the same in all environments, including timeouts, thread pools, retry thresholds, etc.

Expose Application Metrics and Information

If we want to put this microservice into production, how will we monitor

it? How can we get any insight about how things are running? Often

our microservices are black boxes unless we explicitly think through how

we want to expose metrics to the outside world. Fortunately, Spring Boot comes with a

prepackaged starter (

spring-boot-starter-actuator

) that makes doing this a breeze.

Let’s see what it takes to enable the actuator. Open up the

pom.xml

file for your

hello-springboot

microservice and add the following Maven

dependency in the

<dependencies>...</dependencies>

section:

<dependency><groupId>org.springframework.boot</groupId><artifactId>spring-boot-starter-actuator</artifactId></dependency>

Because we’ve added the actuator dependency, our application now can expose a lot of information that will be very handy for debugging or general microservice insight.

Not all endpoints provided by the actuator dependency are exposed by default, however. We need to manually specify which endpoints will be exposed.

Add the following property to src/main/resources/application.properties to expose some technology-agnostic endpoints:

#Enablemanagementendpointsmanagement.endpoints.web.exposure.include=beans,env,health,metrics,httptrace,mappings

Now restart your microservice by stopping it and running:

$ mvn clean spring-boot:run

Try hitting the following URLs and examine what gets returned:

-

http://localhost:8080/actuator/beans

-

http://localhost:8080/actuator/env

-

http://localhost:8080/actuator/health

-

http://localhost:8080/actuator/metrics

-

http://localhost:8080/actuator/httptrace

-

http://localhost:8080/actuator/mappings

Figure 2-4 shows an example of what the http://localhost:8080/env endpoint looks like.

Figure 2-4. Actuator response

Exposing runtime insights like this frees up the developer to just focus on writing code for the microservice that delivers business value. Delegating the heavy lifting and boilerplate to frameworks is definitely a good idea.

Running Outside of Maven

Up to this point we’ve been thinking about development and building our Hello World microservice from the perspective of a developer’s laptop using Maven. But what if you want to distribute your microservice to others or run it in a live environment (development, QA, production)?

Luckily, with Spring Boot it only takes a few steps to get

ready for shipment and production. Spring Boot prefers atomic, executable JARs with all dependencies packed into a flat classpath. This means the JAR that we create as part of a call to

mvn clean package

is

executable and contains all we need to run our microservice in a Java

environment. To test this out, go to the root of the

hello-springboot

microservice project and run the following commands:

$ mvn clean package $ ava -jar target/hello-springboot-1.0.jar

If your project was named demo instead of hello-springboot , then substitute the properly named JAR file ( demo-1.0.jar ).

That’s it!

We’ll notice this sort of idiom when we explore MicroProfile in the next chapter, too.

Calling Another Service

In a microservices environment, each service is responsible for providing its functionality or service to other collaborators. As we discussed in the first chapter, building distributed systems is hard, and we cannot abstract away the network or the potential for failures. We will cover how to build resilient interactions with our dependencies in Chapter 5 . In this section, however, we will just focus on getting a service to talk to a dependent service.

If we wish to extend the hello-springboot microservice, we will need to create a service that we can call using Spring’s REST client functionality. For this example and the rest of the examples in the report, we’ll use a backend service and modify our service to reach out to the backend to generate the greetings we want to be able to use, as indicated by Figure 2-5 .

Figure 2-5. Calling another service

If you look at the

source code for this report

, you’ll see a Maven module called

backend

that contains a very simple

HTTP servlet that can be invoked with a GET request and query

parameters. The code for this backend is very simple, and it does not use

any of the microservice frameworks (Spring Boot, MicroProfile etc.). We have created a

ResponseDTO

object that encapsulates

time

,

ip

, and

greeting

fields. We also leverage the awesome Jackson

library for JSON data binding, as seen here:

@WebServlet(urlPatterns={"/api/backend"})publicclassBackendHttpServletextendsHttpServlet{@OverrideprotectedvoiddoGet(HttpServletRequestreq,HttpServletResponseresp)throwsServletException,IOException{resp.setContentType("application/json");ObjectMappermapper=newObjectMapper();Stringgreeting=req.getParameter("greeting");ResponseDTOresponse=newResponseDTO();response.setGreeting(greeting+" from cluster Backend");response.setTime(System.currentTimeMillis());response.setIp(getIp());PrintWriterout=resp.getWriter();mapper.writerWithDefaultPrettyPrinter().writeValue(out,response);}privateStringgetIp(){Stringhostname=null;try{hostname=InetAddress.getLocalHost().getHostAddress();}catch(UnknownHostExceptione){hostname="unknown";}returnhostname;}}

To start up the backend service on port

8080

, navigate to the

backend

directory and run the following command:

$ mvn wildfly:run

The

backend

project uses the Maven WildFly plug-in, which allows us to

quickly boot up our app using

mvn wildfly:run

.

This service is exposed at

/api/backend

and takes a query parameter called

greeting

. For example, when we call this service with the path

/api/backend?greeting=Hello

, like this (you can also visit this URL with your browser):

$ curl -X GET http://localhost:8080/api/backend?greeting=Hello

Then the backend service will respond with a JSON object something like this:

{"greeting":"Hello from cluster Backend","time":1459189860895,"ip":"172.20.10.3"}

Next, we’ll create a new HTTP endpoint, /api/greeting , in our hello-springboot microservice and use Spring to call this backend.

First, we create a class in

src/main/java/com/examples/hellospringboot

called

GreeterRestController

and fill it in similarly to how we filled in the

HelloRestController

class (see

Example 2-4

).

Example 2-4. src/main/java/com/example/hellospringboot/GreeterRestController.java

@RestController@RequestMapping("/api")@ConfigurationProperties(prefix="greeting")publicclassGreeterRestController{privateStringsaying;privateStringbackendServiceHost;privateintbackendServicePort;@RequestMapping(value="/greeting",method=RequestMethod.GET,produces="text/plain")publicStringgreeting(){StringbackendServiceUrl=String.format("http://%s:%d/api/backend?greeting={greeting}",backendServiceHost,backendServicePort);System.out.println("Sending to: "+backendServiceUrl);returnbackendServiceUrl;}}

We’ve left out the setters for the properties in this class, but

make sure you have them in your source code

! Note that we are using the

@ConfigurationProperties

annotation again to configure the REST controller here, although this time we are

using the

greeting

prefix. We also create a GET endpoint, like we did

with the

hello

service; and all it returns at the moment is a string

with the values of the backend service host and port concatenated

(these values are injected in via the

@ConfigurationProperties

annotation). Let’s add the

backendServiceHost

and

backendServicePort

to our

application.properties

file:

greeting.saying=Hello Spring Boot greeting.backendServiceHost=localhost greeting.backendServicePort=8080

Next, we’re going to use Spring’s

RestTemplate

to do the invocation of

the remote service. Following a long-lived Spring convention with its

template patterns, the

RestTemplate

wraps common HTTP/REST idioms inside a convenient wrapper abstraction which then handles all the

connections and marshalling/unmarshalling the results of an invocation.

RestTemplate

uses the native JDK for HTTP/network access, but you can

swap that out for Apache HttpComponents, OkHttp, Netty, or others.

Example 2-5

shows what the source looks like when using the

RestTemplate

(again,

the getters/setters are omitted here, but required). We are communicating with

the backend service by constructing a URL based on the host and port

that have been injected, and we add a GET query parameter called

greeting

. The value we send to the backend service for the

greeting

parameter is from the

saying

field of the

GreeterRestController

object, which gets injected as part of the configuration when we add

the

@ConfigurationProperties

annotation.

Example 2-5. src/main/java/com/example/GreeterRestController.java

@RestController@RequestMapping("/api")@ConfigurationProperties(prefix="greeting")publicclassGreeterRestController{privateRestTemplatetemplate=newRestTemplate();privateStringsaying;privateStringbackendServiceHost;privateintbackendServicePort;@RequestMapping(value="/greeting",method=RequestMethod.GET,produces="text/plain")publicStringgreeting(){StringbackendServiceUrl=String.format("http://%s:%d/api/backend?greeting={greeting}",backendServiceHost,backendServicePort);System.out.println("Sending to: "+backendServiceUrl);BackendDTOresponse=template.getForObject(backendServiceUrl,BackendDTO.class,saying);returnresponse.getGreeting()+" at host: "+response.getIp();}}

Next, we add the

BackendDTO

class, which is used to encapsulate

responses from the backend (

Example 2-6

).

Example 2-6. src/main/java/com/examples/hellospringboot/BackendDTO.java

publicclassBackendDTO{privateStringgreeting;privatelongtime;privateStringip;publicStringgetGreeting(){returngreeting;}publicvoidsetGreeting(Stringgreeting){this.greeting=greeting;}publiclonggetTime(){returntime;}publicvoidsetTime(longtime){this.time=time;}publicStringgetIp(){returnip;}publicvoidsetIp(Stringip){this.ip=ip;}}

Now let’s build the microservice and verify that we can call this new greeting endpoint and that it properly calls the backend. First, start the backend if it’s not already running. Navigate to the backend directory of the source code that comes with this application and run it:

$ mvn clean wildfly:run

Next, we’ll build and run the Spring Boot microservice. Let’s also

configure this service to run on a different port than the default port

(

8080

) so that it doesn’t collide with the backend service, which is

already running on port

8080

:

$ mvn clean spring-boot:run -Dserver.port=9090

Later in the report we’ll see how running these microservices in their own Linux container removes the restriction of port swizzling at runtime.

Now, point your browser to http://localhost:9090/api/greeting to see if the microservice properly calls the backend and displays what we’re expecting, as shown in Figure 2-6 .

Figure 2-6. Successful backend

Where to Look Next

In this chapter, you learned what Spring Boot is and how it’s different from traditional WAR/EAR deployments. You also saw some simple use cases, including exposing an HTTP/REST endpoint, externalizing configuration, exposing metrics, and calling another service. This is just scratching the surface; if you’re interested in learning more about Spring Boot, please take a look at the following references:

Chapter 3. Eclipse MicroProfile for Microservices

The next Java microservice framework we’ll look at is MicroProfile.

Java Enterprise Edition (EE) (now Jakarta EE) has been the workhorse of enterprise Java applications for more than 15 years. Many enterprises have heavily invested in open source and proprietary Java EE technologies, and this has affected everything from how they hire software talent to training, tooling, and management. Java EE has always been very capable at helping developers build tiered applications by offering functionality like servlets/JavaServer Pages (JSPs), transactions, component models, messaging, and persistence.

Despite its popularity, recently the feeling began to grow that Java EE’s pace of innovation was too slow for a world that demanded cloud-native applications, microservices, and containers. This feeling prompted various Java User Groups, Java Champions, vendors, and corporations to join forces and release the MicroProfile specification.

MicroProfile 1.0, announced during JavaOne 2016, was composed of the CDI, JSON-P, and JAX-RS specifications from Java EE. These base APIs allow experienced Java EE developers to utilize their existing skill sets for this fast-paced, innovative, and open source specification.

As a specification, there are several MicroProfile implementations: these include Thorntail from Red Hat, Payara Micro from Payara, TomEE from Apache, and OpenLiberty from IBM, just to name a few.

Because Java EE had a strong influence on MicroProfile, it is worth mentioning that in 2017, Oracle donated Java EE to the Eclipse Foundation under the Jakarta EE brand. Although Jakarta EE and MicroProfile share the same origin, their purpose remains very different. While Jakarta EE is a continuation of Java EE and focuses on enterprise applications, MicroProfile instead focuses on Enterprise microservices applications.

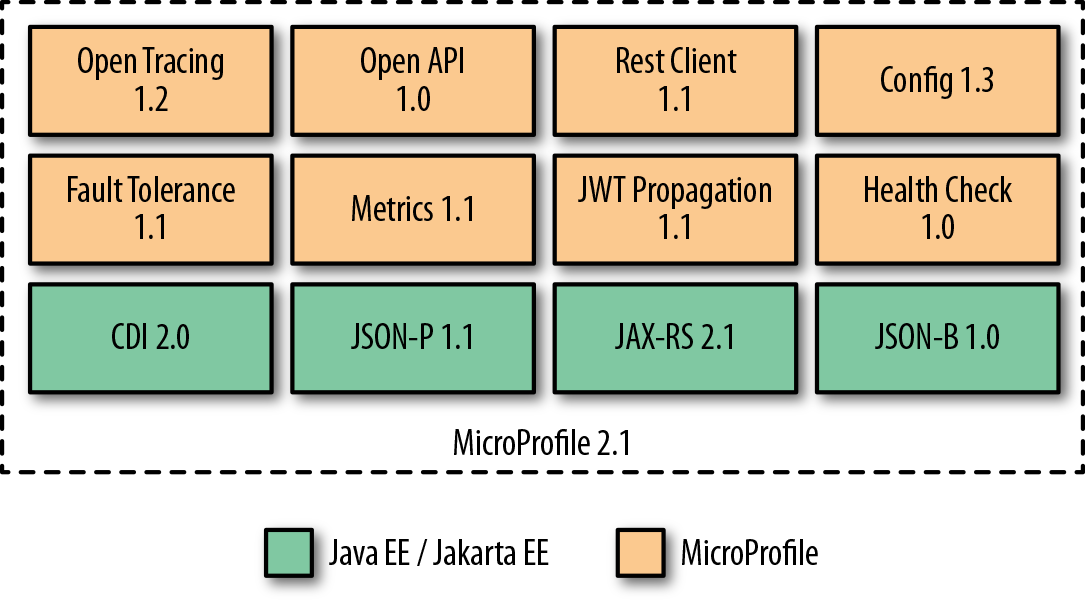

The MicroProfile 2.1 specification defines the base programming model using the Jakarta EE CDI, JSON-P, JAX-RS, and JSON-B APIs, and adds Open Tracing, Open API, Rest Client, Config, Fault Tolerance, Metrics, JWT Propagation, and Health Check APIs (see Figure 3-1 ). Development remains active, with groups working on Reactive Streams, Reactive Messaging, GraphQL, long running actions, and service mesh features.

Figure 3-1. MicroProfile 2.1 APIs

Thorntail

Thorntail is the MicroProfile implementation from Red Hat. It is a complete teardown of the WildFly application server into bite-sized, reusable components that can be assembled and formed into a microservice application. Assembling these components is as simple as including a dependency in your Java Maven (or Gradle) build file; Thorntail takes care of the rest.

Thorntail evaluates your pom.xml (or Gradle) file and determines what dependencies your microservice actually uses (e.g., CDI, OpenTracing, and Metrics), and then builds an uber-JAR (just like Spring Boot and Dropwizard) that includes the minimal APIs and implementations necessary to run your service.

Besides the MicroProfile API, Thorntail provides many other functionalities. Some components provide only access to other APIs, such as JPA or JMS; other components provide higher-level capabilities, such as integration with Infinispan.

Getting Started

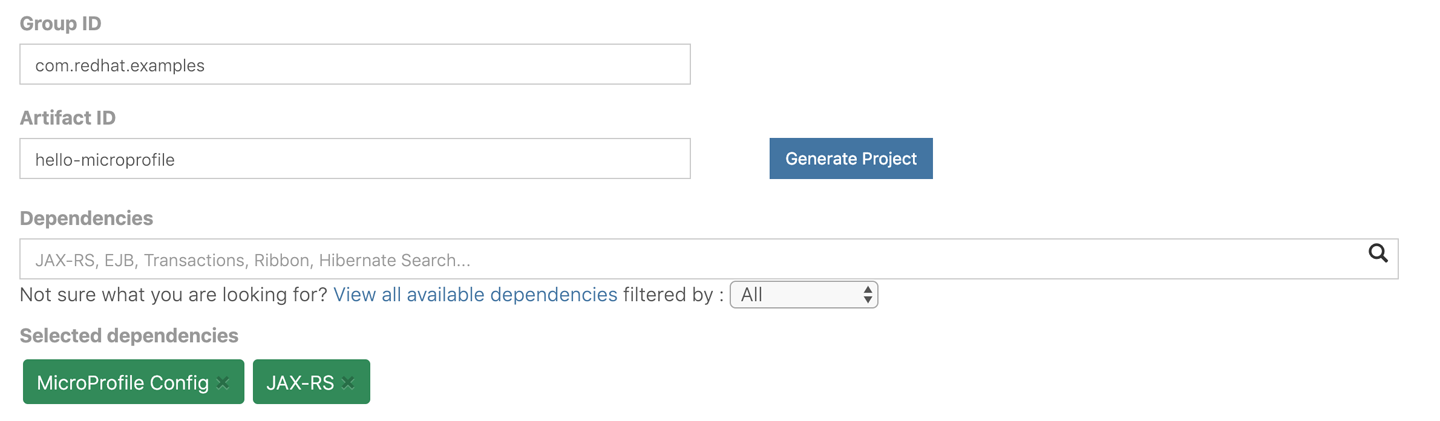

You can start a new Thorntail project by using the Thorntail Generator web console to bootstrap it (similar to Spring Initializr for Spring Boot). Simply open the page and fill in the fields with the following values, as shown in Figure 3-2 :

-

Group ID: com.redhat.examples

-

Artifact ID: hello-microprofile

-

Dependencies: MicroProfile Config, JAX-RS

Figure 3-2. Thorntail Generator

Now click the blue Generate Project button. This will cause a file called hello-microprofile.zip to be downloaded. Save the file and extract it.

Navigate to the hello-microprofile directory, and try running the following command:

$ mvn thorntail:run

Make sure that you have stopped the

backend

service that you started in the previous chapter.

If everything boots up without any errors, you should see some logging similar to this:

2018-12-14 15:23:54,119 INFO [org.jboss.as.server] (main)

WFLYSRV0010: Deployed "demo.war" (runtime-name : "demo.war")

2018-12-14 15:23:54,129 INFO [org.wildfly.swarm] (main)

THORN99999: Thorntail is Ready

Congrats! You have just gotten your first MicroProfile application up and running. If you navigate to http://localhost:8080/hello in your browser, you should see the output shown in Figure 3-3 .

Figure 3-3. Hello from Thorntail

Hello World

Just like with the Spring Boot framework in the preceding chapter, we want to add some basic “Hello World” functionality and then incrementally add more functionality on top of it.

We want to expose an HTTP/REST endpoint at

/api/hello

that will return “Hello MicroProfile from

X

,” where

X

is the IP

address where the service is running. To do this, navigate to

src/main/java/com/examples/hellomicroprofile/rest

. This location should have been created for

you if you followed the preceding steps. Then create a new Java class called

HelloRestController

, as shown in

Example 3-1

. We’ll add a method named

hello()

that returns a string along with the IP address of where the service is running. You’ll see in

Chapter 6

, in the sections on load balancing and service discovery, how the host IPs can be used to demonstrate proper failover, load balancing, etc.

Example 3-1. src/main/java/com/examples/hellomicroprofile/rest/HelloRestController.java

publicclassHelloRestController{publicStringhello(){Stringhostname=null;try{hostname=InetAddress.getLocalHost().getHostAddress();}catch(UnknownHostExceptione){hostname="unknown";}return"Hello MicroProfile from "+hostname;}}

Add the HTTP Endpoints

You might have noticed that the POJO class

HelloRestController

in the MicroProfile project has exactly the same implementation as the

HelloRestController

class in the Spring Boot project. The only exception will be the HTTP endpoint annotations, which we add in

Example 3-2

:

-

@Path -

Maps specific parts of the HTTP URI path to classes and methods.

-

@GET -

Specifies that any HTTP GET method will invoke the annotated method. The method won’t be called if the path is the same but the HTTP method is anything other than GET.

-

@Produces -

Specifies the MIME type of the response.

Again, note that import statements are omitted in the following example.

Example 3-2. src/main/java/com/examples/hellospringboot/HelloRestController.java

@Path("/api")publicclassHelloRestController{@GET@Produces("text/plain")@Path("/hello")publicStringhello(){Stringhostname=null;try{hostname=InetAddress.getLocalHost().getHostAddress();}catch(UnknownHostExceptione){hostname="unknown";}return"Hello MicroProfile from "+hostname;}}

In this code, all we’ve done is add the aforementioned annotations. For

example,

@Path("/api")

at the class level says “map any

method-level HTTP endpoints under this root URI path.” When we add

@Path("/hello")

and

@GET

, we are telling MicroProfile to expose an HTTP GET endpoint at

/hello

(which will really be

/api/hello

). The annotation

@Produces("text/plain")

maps requests with a media type of

Accept: text/plain

to this method.

If you build the application and run

thorntail:run

again, you should

be able to reach the HTTP endpoint:

$ mvn clean thorntail:run

Now if you point your browser to http://localhost:8080/api/hello , you should see a response similar to the one shown in Figure 3-4 .

Figure 3-4. Successful hello

Now, the same way as we did for Spring Boot, we will see how to inject external properties into our app using MicroProfile’s Config API.

Externalize Configuration

Like Spring Boot, MicroProfile defines a mechanism to

externalize configuration. It uses different

ConfigSource

s to consume configuration from system properties, environment variables, or even from a

META-INF/microprofile-config.properties

file. Each of

these sources has a different priority, so configuration values can be overwritten.

To see how simple it is to consume external configuration, let’s add a new property to our src/main/resources/META-INF/microprofile-config.properties file (remember to create the folder structure and the file if they don’t exist):

helloapp.saying=Guten Tag aus

Now, as shown in

Example 3-3

, let’s add the

@Inject

and

@ConfigProperty("helloapp.saying")

annotations and our new

saying

field to the

HelloRestController

class. Note that, unlike with Spring Boot, we don’t need setters or getters.

Example 3-3. src/main/java/com/examples/hellomicroprofile/HelloRestController.java

@Path("/api")publicclassHelloRestController{@Inject@ConfigProperty(name="helloapp.saying")privateStringsaying;@GET@Produces("text/plain")@Path("/hello")publicStringhello(){Stringhostname=null;try{hostname=InetAddress.getLocalHost().getHostAddress();}catch(UnknownHostExceptione){hostname="unknown";}returnsaying+" "+hostname;}}

Because we’ve started using the CDI API in our examples, we’ll also need to add the beans.xml file, with the contents shown in Example 3-4 .

Example 3-4. src/main/resources/META-INF/beans.xml

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?><beansxmlns="http://xmlns.jcp.org/xml/ns/javaee"xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"xsi:schemaLocation="http://xmlns.jcp.org/xml/ns/javaeehttp://xmlns.jcp.org/xml/ns/javaee/beans_1_1.xsd"bean-discovery-mode="all"></beans>

This file will instruct the CDI API to process all the injection points marked with the

@Inject

annotation.

Let’s stop our application from running (if we haven’t) and restart it:

$ mvn clean thorntail:run

Now if we navigate to http://localhost:8080/api/hello we should see the German version of the saying, as shown in Figure 3-5 .

Figure 3-5. Successful German hello

Expose Application Metrics and Information

Another similarity with Spring Boot is the ability of MicroProfile applications to expose endpoints that can be used to monitor our applications. To enable this, we need to add the MicroProfile Metrics dependency to our pom.xml file.

Open up the pom.xml file for the hello-microprofile microservice and add the following Maven dependency within the <dependencies>…</dependencies> section:

<dependency><groupId>io.thorntail</groupId><artifactId>microprofile-metrics</artifactId></dependency>

Adding this dependency will cause the application to expose a lot of information that will be very handy for debugging and general insight.

Now stop your microservice and restart it by running:

$ mvn clean thorntail:run

Try hitting the URL http://localhost:8080/metrics and examine what gets returned. You should see something like the result in Figure 3-6 .

Figure 3-6. MicroProfile metrics

Easy, right?

Running Outside of Maven

Remember how easy it was to run Spring Boot outside Maven? Luckily, with MicroProfile it just takes the exact same few steps to get a microservice ready for shipment and production.

Just like Spring Boot, MicroProfile prefers atomic, executable JARs with all dependencies packed into a flat classpath. This means the JAR that we create as part of a call to

mvn clean package

is

executable and contains all we need to run our microservice in a Java

environment! To test this out, go to the root of the

hello-microprofile

microservice project and run the following commands:

$ mvn clean package $ java -jar target/demo-thorntail.jar

That’s it! Exactly the same approach used by Spring Boot.

Calling Another Service

In a microservices environment, each service is responsible for providing its functionality or service to other collaborators. If we wish to extend the hello_microprofile microservice, we will need to create a service that we can call using JAX-RS client functionality. Just like we did for the Spring Boot microservice, we’ll leverage the backend service from the source code that accompanies this report. The interaction will look similar to Figure 3-7 .

Figure 3-7. Calling another service

If you look at the

source code for this report

, you’ll see a Maven module called

backend

which contains a very simple

HTTP servlet that can be invoked with a GET request and query

parameters. The code for this backend is very simple, and it does not use

any of the microservice frameworks (Spring Boot, MicroProfile, etc.).

To start up the backend service on port

8080

, navigate to the

backend

directory and run the following:

$ mvn clean wildfly:run

Remember that the hello-microprofile service should be stopped before running the backend service.

This service is exposed at

/api/backend

and takes a query parameter called

greeting

. For example, when we call this service with the path

/api/backend?greeting=Hello

, like this (you can also visit this URL with your browser):

$ curl -X GET http://localhost:8080/api/backend?greeting=Hello

We get back a JSON object like this:

{"greeting":"Hello from cluster Backend","time":1459189860895,"ip":"172.20.10.3"}

Next, we’ll create a new HTTP endpoint, /api/greeting , in our hello-microprofile microservice and use the JAX-RS Client API to call this backend.

First, we create a new class in

src/main/java/com/examples/hellomicroprofile

called

GreeterRestController

and fill it in similarly to how we filled in the

HelloRestController

class (see

Example 3-5

).

Example 3-5. src/main/java/com/example/hellomicroprofile/rest/GreeterRestController.java

@Path("/api")publicclassGreeterRestController{@Inject@ConfigProperty(name="greeting.saying",defaultValue="Hello")privateStringsaying;@Inject@ConfigProperty(name="greeting.backendServiceHost",defaultValue="localhost")privateStringbackendServiceHost;@Inject@ConfigProperty(name="greeting.backendServicePort",defaultValue="8080")privateintbackendServicePort;@GET@Produces("text/plain")@Path("greeting")publicStringgreeting(){StringbackendServiceUrl=String.format("http://%s:%d",backendServiceHost,backendServicePort);return"Sending to: "+backendServiceUrl}}

We’ve created a simple JAX-RS resource here that exposes an

/api/greeting

endpoint that just returns the value of the

backendServiceUrl

field. Also note that we’re injecting the backend host and port as environment variables that have default values if no environment variables are set. Again, we’re using MicroProfile Config’s

@ConfigProperty

annotation to accomplish this.

Let’s also add the

BackendDTO

class, shown in

Example 3-6

, which is used to encapsulate responses from the backend.

Example 3-6. src/main/java/com/examples/hellomicroprofile/BackendDTO.java

publicclassBackendDTO{privateStringgreeting;privatelongtime;privateStringip;publicStringgetGreeting(){returngreeting;}publicvoidsetGreeting(Stringgreeting){this.greeting=greeting;}publiclonggetTime(){returntime;}publicvoidsetTime(longtime){this.time=time;}publicStringgetIp(){returnip;}publicvoidsetIp(Stringip){this.ip=ip;}}

Next, let’s add our JAX-RS client implementation to communicate with the backend service. It should look like Example 3-7 .

Example 3-7. src/main/java/com/example/hellospringboot/GreeterRestController.java

@Path("/api")publicclassGreeterRestController{@Inject@ConfigProperty(name="greeting.saying",defaultValue="Hello")privateStringsaying;@Inject@ConfigProperty(name="greeting.backendServiceHost",defaultValue="localhost")privateStringbackendServiceHost;@Inject@ConfigProperty(name="greeting.backendServicePort",defaultValue="8080")privateintbackendServicePort;@GET@Produces("text/plain")@Path("greeting")publicStringgreeting(){StringbackendServiceUrl=String.format("http://%s:%d",backendServiceHost,backendServicePort);System.out.println("Sending to: "+backendServiceUrl);Clientclient=ClientBuilder.newClient();BackendDTObackendDTO=client.target(backendServiceUrl).path("api").path("backend").queryParam("greeting",saying).request(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON_TYPE).get(BackendDTO.class);returnbackendDTO.getGreeting()+" at host: "+backendDTO.getIp();}}

Now let’s build the microservice and verify that we can call this new

greeting endpoint and that it properly calls the backend. We’ll

configure this service to run on a different port than the default

(

8080

) so that it doesn’t collide with the backend service, which is

already running on that port:

$ mvn thorntail:run \ -Dswarm.network.socket-binding-groups.standard-sockets .port-offset=100

In Chapter 6 , we’ll see how running these microservices in their own Linux containers removes the restriction of port swizzling at runtime. With all that done, you can point your browser to http://localhost:8180/api/greeting to see if our microservice properly calls the backend and displays what we’re expecting, as shown in Figure 3-8 .

Figure 3-8. Successful backend

Where to Look Next