- Cover

- Introduction

- 1 Hello, Android

- 2 Getting Started

- 3 Applications and Activities and Fragments, Oh My!

- 4 Defining the Android Manifest and Gradle Build Files, and Externalizing Resources

- 5 Building User Interfaces

- 6 Intents and Broadcast Receivers

- 7 Using Internet Resources

-

8 Files, Saving State, and User Preferences

- SAVING FILES, STATES, AND PREFERENCES

- SAVING AND RESTORING ACTIVITY AND FRAGMENT INSTANCE STATE USING THE LIFECYCLE HANDLERS

- RETAINING INSTANCE STATE WITH HEADLESS FRAGMENTS AND VIEW MODELS

- CREATING AND SAVING SHARED PREFERENCES

- RETRIEVING SHARED PREFERENCES

- INTRODUCING ON SHARED PREFERENCE CHANGE LISTENERS

- CONFIGURING AUTO BACKUP OF APPLICATION FILES AND SHARED PREFERENCES

- BUILDING A PREFERENCE UI

- CREATING A SETTINGS ACTIVITY FOR THE EARTHQUAKE MONITOR

- INCLUDING STATIC FILES AS RESOURCES

- WORKING WITH THE FILESYSTEM

- SHARING FILES USING FILE PROVIDER

- ACCESSING FILES FROM OTHER APPLICATIONS USING THE STORAGE ACCESS FRAMEWORK

- USING URI-BASED PERMISSIONS

- 9 Creating and Using Databases

- 10 Content Providers and Search

- 11 Working in the Background

- 12 Implementing the Android Design Philosophy

-

13 Implementing a Modern Android User Experience

- THE MODERN ANDROID UI

- CREATING CONSISTENT, MODERN USER INTERFACES USING APPCOMPAT

- ADDING A MENU AND ACTIONS TO THE APP BAR

- GOING BEYOND THE DEFAULT APP BAR

- IMPROVING THE EARTHQUAKE MONITOR’S APP BAR

- APP NAVIGATION PATTERNS

- ADDING TABS TO THE EARTHQUAKE MONITOR

- CHOOSING THE RIGHT LEVEL OF INTERRUPTION

- 14 Advanced Customization of Your User Interface

-

15 Location, Contextual Awareness, and Mapping

- ADDING LOCATION, MAPS, AND CONTEXTUAL AWARENESS TO YOUR APPLICATIONS

- INTRODUCING GOOGLE PLAY SERVICES

- FINDING DEVICE LOCATION USING GOOGLE LOCATION SERVICES

- SETTING AND MANAGING GEOFENCES

- USING THE LEGACY PLATFORM LOCATION-BASED SERVICES

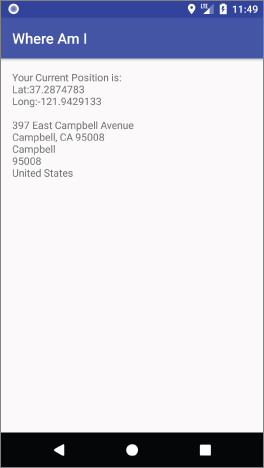

- USING THE GEOCODER

- CREATING MAP-BASED ACTIVITIES

- MAPPING THE EARTHQUAKE EXAMPLE

- ADDING CONTEXTUAL AWARENESS

- 16 Hardware Sensors

- 17 Audio, Video, and Using the Camera

- 18 Communicating with Bluetooth, NFC, and Wi-Fi Peer-to-Peer

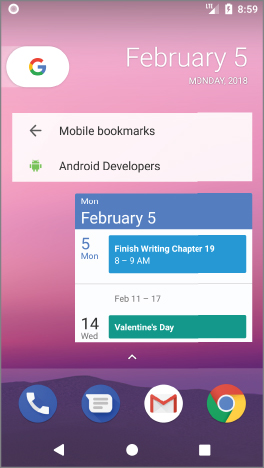

- 19 Invading the Home Screen

- 20 Advanced Android Development

-

21 Releasing, Distributing, and Monitoring Applications

- PREPARING FOR RELEASE

- UPDATING APPLICATION METADATA IN YOUR APPLICATION MANIFEST

- SIGNING PRODUCTION BUILDS OF YOUR APPLICATION

- DISTRIBUTING YOUR APPLICATION ON THE GOOGLE PLAY STORE

- AN INTRODUCTION TO MONETIZING APPLICATIONS

- APPLICATION MARKETING, PROMOTION, AND DISTRIBUTION STRATEGIES

- USING FIREBASE TO MONITOR YOUR APPLICATION

- Index

- End User License Agreement

PROFESSIONAL Android®

Fourth Edition

INTRODUCTION

For many people, smartphones have become an extension of themselves. Now running on over 2 billion monthly-active devices, Android is the most common smartphone operating system in use world-wide, with users installing an average of 50 apps each, resulting in over 94 billion apps downloaded from the Play app store in 2017 alone.

Ubiquitous and indispensable, smartphones are so advanced and personal that studies have shown people become anxious if they misplace their device, lose connectivity, or run low on battery.

In the 10 years since launching in 2008, Android has expanded beyond mobile phones to become a development platform for a wide range of hardware, with 24,000 devices from over 1,300 brands, including everything from tablets to televisions, watches, cars, and Internet of Things (IoT) devices. Over the same period, there have been 28 platform and SDK releases.

These innovations, combined with the size of the ecosystem, provide unparalleled opportunities for developers to create innovative new applications for a global audience of users.

Android offers an open platform for mobile application development. Without artificial barriers, Android developers are free to write apps that take full advantage of an incredible range of devices. Using Google Play for distribution, developers can distribute free and paid applications to compatible Android devices globally.

This book is a hands-on guide to building Android applications for all Android devices. It’s written based on version 8.1 of the Android SDK, using Android Studio 3.1. Chapter by chapter, it takes you through a series of sample projects, each introducing new features and techniques to get the most out of Android. It covers all the basic functionality to get started, as well as the information for experienced mobile developers to take full advantage of the features of Android, to enhance existing products or create innovative new ones.

The Android team releases a new major platform every year, a new version of Android Studio every few months, and incremental changes to Jetpack, such as the support library and Android Architecture Components, many times each year. With such rapid release cycles, there are regular changes, additions, and improvements to the tools, platform APIs, and development libraries you’ll use—and which are described in this book. To minimize the impact of these changes, the Android engineering team works hard to ensure backward compatibility.

However, future releases will date some of the information provided in this book, and not all active Android devices will be running the latest platform release. To mitigate this, wherever possible, we have used backward-compatible support libraries, and included details on which platform releases support the functionality described—and which alternatives may exist to provide support for users of devices running earlier platforms.

Further, the explanations and examples included will give you the grounding and knowledge needed to write compelling mobile applications using the current SDK, along with the flexibility to quickly adapt to future enhancements.

WHO THIS BOOK IS FOR

This book is for anyone interested in creating applications for the Android platform. It includes information that will be valuable, whether you’re an experienced mobile developer on other platforms, making your first foray into writing mobile apps, and if you have some Android development experience.

It will help if you’ve used a smartphone (particularly an Android device), but it’s not necessary, nor is prior experience in mobile application development.

It’s expected that you’ll have experience in software development and be familiar with basic object-oriented paradigms. An understanding of Java syntax is expected, though not a strict necessity.

Chapters 1 and 2 introduce mobile development and the Android development platform, and contain instructions to get you started. Beyond that, there’s no requirement to read the chapters in order, although a good understanding of the core components described in Chapters 3 – 7 is important before you venture into the remaining chapters. Chapter 11 covers important details on how to ensure your apps are responsive and efficient, while Chapters 12 – 14 describe how to provide a rich and consistent user experience. The remaining chapters cover a variety of functionality whose relevance will vary based on your application, and can be read in whatever order interest or need dictates.

WHAT THIS BOOK COVERS

Chapter 1 introduces Android, including what it is and how it fits into the mobile development ecosystem. What Android offers as a development platform and why it’s an exciting opportunity for creating mobile phone applications are then examined in greater detail.

Chapter 2 covers some best practices for mobile development and explains how to download and install Android Studio and the Android SDK. It then introduces some of the tools and features included with Android Studio, and demonstrates how they can be used to create and debug new applications.

Chapters 3 – 7 take an in-depth look at the fundamental Android application components—starting by examining the components that make up an Android application, and then moving on to “Activities” and “Fragments,” and their associated lifetimes and lifecycles.

You’ll then be introduced to the application manifest and the Gradle build system, before learning more about the external resource framework used to support devices used in different counties, with different languages, and in a variety of shapes and sizes.

You’ll learn how to create basic user interfaces with layouts, Views, and Fragments, before being introduced to the Intent and Broadcast Receiver mechanisms used to perform actions and send messages between application components. Accessing Internet resources is then covered, followed by a detailed look at data storage, retrieval, and sharing. You’ll start with the preference-saving mechanism and then move on to file handling, databases, and Content Providers—including accessing data from the native databases.

This section finishes with an examination of how to ensure your app is always responsive, and is efficient in its use of battery when running in the background. You’ll be introduced to threading APIs that enable asynchronous execution, and mechanisms that support efficient scheduling of background work. You’ll also learn how to create and display interactive Notifications.

Chapters 12 – 14 build on the UI framework introduced in Chapter 5 . You’ll learn to enhance the user experience through the principles of material design and to make your applications accessible and optimized for a variety of screen sizes and resolutions. You’ll further improve the user experience by understanding the variety of navigation options available, adding movement through animations, and the use of Toolbars and Menus.

Chapters 15 – 19 look at more advanced topics. You’ll learn how to use Google Play services to add interactive maps, find the user’s location, and how to create geo- and awareness-fences. Using movement and environmental Sensors—including the compass, accelerometers, and the barometer—you’ll make your applications react to their environment.

After looking at how to play and record multimedia, as well as how to use the camera to take pictures and record video, you’ll be introduced to Android’s communication capabilities, including Bluetooth, NFC, and Wi-Fi Direct. Next, you’ll learn how your applications can interact with users directly from the home screen using dynamic Widgets, Live Wallpaper, and the Application Shortcuts.

Chapter 20 discusses several advanced development topics, including security, using the fingerprint sensor, and Strict Mode, followed by the telephony APIs and the APIs used to send and receive SMS messages.

Finally, Chapter 21 examines the process for building, releasing, monitoring, and monetizing your applications. In particular, it includes details for publishing and distributing your applications within Google Play.

HOW THIS BOOK IS STRUCTURED

This book is structured in a logical sequence to help readers of different development backgrounds learn how to write advanced Android applications. There’s no requirement to read each chapter sequentially, but several of the sample projects are developed over the course of multiple chapters, adding new functionality and other enhancements at each stage.

Experienced mobile developers who have already installed Android Studio, and those with a working knowledge of Android development, can skim the first two chapters—which are an introduction to mobile development and instructions for creating your development environment—and then dive in at Chapters 3 – 7 . These chapters cover the fundamentals of Android development, so it’s important to have a solid understanding of the concepts they describe.

With this covered, you can move on to the remaining chapters, which look at material design, maps, location-based services, background applications, and more advanced topics, such as hardware interaction and networking.

WHAT YOU NEED TO USE THIS BOOK

To use the code samples in this book, you will need to create an Android development environment by downloading Android Studio and the Android SDK. It’s also possible to use other IDEs, or even to build your apps from the command-line. We’ll assume, however, you’re using Android Studio.

Android development is supported on Windows, macOS, and Linux, with Android Studio and the SDK available from the Android website.

You do not need an Android device to use this book or develop Android applications—though it can be useful, particularly when testing.

CONVENTIONS

To help you get the most from the text and keep track of what’s happening, we’ve used a number of conventions throughout the book.

As for styles in the text:

-

We show file names, URLs, and code within the text like so:

persistence.properties. - To help readability, class names in text are often represented using a regular font but capitalized like so: Content Provider.

-

We present code in two different ways:

We use a monofont type with no highlighting for most code examples.We use bold to indicate changes or additions from a similar previous code snippet. -

In some code samples, you’ll see lines marked as follows:

[… Existing code …]or

[… Implement something here …]These represent instructions to replace the entire line (including the square brackets) with actual code, either from a previous code snippet (in the former case) or with your own implementation (in the latter).

-

To keep the code samples reasonably concise, we have not always included every

packagedefinition orimportstatement required in the code snippets. The downloadable code samples described below include all the requiredimportstatements. Additionally, if you are developing using Android Studio, you can enable auto-import or use the keyboard shortcut Ctrl+Space (Cmd+Space) to add the requiredimportstatements.

SOURCE CODE

As you work through the examples in this book, you may choose either to type in all the code manually, or to use the source code files that accompany the book. All the source code used in this book is available for download at

www.wrox.com

. When at the site, simply locate the book’s title (use the Search box or one of the title lists) and click the Download Code link on the book’s detail page to obtain all the source code for the book.

Once you download the code, just decompress it with your favorite compression tool. Alternately, you can go to the main Wrox code download page at

www.wrox.com/dynamic/books/download.aspx

to see the code available for this book and all other Wrox books.

ERRATA

We make every effort to ensure that there are no errors in the text or in the code. However, no one is perfect, and mistakes do occur. If you find an error in one of our books, like a spelling mistake or faulty piece of code, we would be very grateful for your feedback. By sending in errata, you may save another reader hours of frustration, and at the same time, you will be helping us provide even higher quality information.

To find the errata page for this book, go to

www.wrox.com

and locate the title using the Search box or one of the title lists. Then, on the book details page, click the Book Errata link. On this page, you can view all errata that has been submitted for this book and posted by Wrox editors. A complete

book list, including links to each book’s errata, is also available at

www.wrox.com/misc-pages/booklist.shtml

.

If you don’t spot “your” error on the Book Errata page, go to

www.wrox.com/contact/techsupport.shtml

and complete the form there to send us the error you have found. We’ll check the information and, if appropriate, post a message to the book’s errata page and fix the problem in subsequent editions of the book.

1

Hello, Android

ANDROID APPLICATION DEVELOPMENT

Whether you’re an experienced mobile engineer, a desktop or web developer, or a complete programming novice, Android represents an exciting opportunity to write applications for an audience of over two billion Android device users.

You’re probably already familiar with Android, the most common software powering mobile phones. If not, and you purchased this book in the hope that Android development would help you create an unstoppable army of emotionless robot warriors on a relentless quest to cleanse the earth of the scourge of humanity, you should reconsider this book purchase (and your life choices.)

When announcing Android at its launch in 2007, Andy Rubin described it as follows:

The first truly open and comprehensive platform for mobile devices. It includes an operating system, user-interface and applications—all of the software to run a mobile phone but without the proprietary obstacles that have hindered mobile innovation.

—WHERE’S MY GPHONE?

( http://googleblog.blogspot.com/2007/11/wheres-my-gphone.html )

Since then, Android has expanded beyond mobile phones to provide a development platform for an increasingly wide range of hardware, including tablets, televisions, watches, cars, and Internet-of-Things (IoT) devices.

Android is an open source software stack that includes an operating system, middleware, and key applications for mobile and embedded devices.

Critically, for us as developers, it also includes a rich set of API libraries that make it possible to write applications that can shape the look, feel, and function of the Android devices on which they run.

In Android, system, bundled, and all third-party applications are written with the same APIs and executed on the same run time. These APIs feature hardware access, video recording, location-based services, support for background services, maps, notifications, sensors, relational databases, inter-application communication, Bluetooth, NFC, and 2D and 3D graphics.

This book describes how to use these APIs to create your own Android applications. In this chapter you learn some guidelines for mobile and embedded hardware development, and are introduced to some of the platform features available to Android developers.

Android has powerful APIs, a huge and diverse ecosystem of users, excellent documentation, a thriving developer community, and has no required costs for development or distribution. As the Android device ecosystem continues to grow, you have the opportunity to create innovative applications for users, no matter what your development experience.

A LITTLE BACKGROUND

In the days before Instagram, Snapchat, and Pokémon Go, when Google was still a twinkle in its founders’ eyes and dinosaurs roamed the earth, mobile phones were just that—portable phones small enough to fit inside a briefcase, featuring batteries that could last up to several hours. They did, however, offer the freedom to make calls without being physically connected to a landline.

In the 10 years since the first Android device was launched, smart phones have become ubiquitous and indispensable. Hardware advancements have made devices more powerful, featuring bigger, brighter screens and featuring advanced hardware including accelerometers, fingerprint scanners, and ultra-high-resolution cameras.

These same advances have more recently resulted in a proliferation of additional form factors for Android devices, including a large variety of smart-phones, tablets, watches, and televisions.

These hardware innovations offer fertile ground for software development, providing many opportunities to create innovative new applications.

The Not-So-Distant Past

In the early days of native phone application development, developers, generally coding in low-level C or C++, needed to understand the specific hardware they were coding for, typically a single device or possibly a range of devices from a single manufacturer. The complexity inherent in this approach meant the applications written for these devices often lagged behind their hardware counterparts. As hardware technology and mobile Internet access have advanced, this closed approach has become outmoded.

The next significant advancement in mobile phone application development was the introduction of Java-hosted MIDlets. MIDlets were executed on a Java virtual machine (JVM), a process that abstracted the underlying hardware and let developers create applications that ran on many devices that supported the Java run time.

Unfortunately, this convenience came at the price of more heavily restricted access to the device hardware. Similarly, it was considered normal for third-party applications to receive different hardware access and execution rights from those given to native applications written by the phone manufacturers, with MIDlets often receiving few of either.

The introduction of Java MIDlets expanded developers’ audiences, but the lack of low-level hardware access and sandboxed execution meant that most mobile applications were regular desktop programs or websites designed to render on a smaller screen, and didn’t take advantage of the inherent mobility of the handheld platform.

Living in the Future

At its introduction, Android was part of a new wave of modern mobile operating systems designed specifically to support application development on increasingly powerful mobile hardware.

Android offers an open development platform built on an open source Linux kernel. Hardware access is available to all applications through a series of API libraries, and application interaction, while carefully controlled, is fully supported.

In Android, all applications have equal standing. Third-party and native Android applications are written with the same APIs and are executed on the same run time. Users can replace most system application with a third-party developer’s alternative; indeed, even the dialer and home screens can be replaced.

THE ANDROID ECOSYSTEM

The Android ecosystem is made up of a combination of three components:

- A free, open source operating system for embedded devices

- An open source development platform for creating applications

- Devices that run the Android operating system (and the applications created for it)

More specifically, Android is made up of several necessary and dependent parts, including the following:

- A Compatibility Definition Document (CDD) and Compatibility Test Suite (CTS) that describe the capabilities required for a device to support the Android software stack.

- A Linux operating system kernel that provides a low-level interface with the hardware, memory management, and process control, all optimized for mobile and embedded devices.

- Open source libraries for application development, including SQLite, WebKit, OpenGL, and a media manager.

- A run time used to execute and host Android applications, including the Android Run Time (ART) and the core libraries that provide Android-specific functionality. The run time is designed to be small and efficient for use on embedded devices.

- An application framework that agnostically exposes system services to the application layer, including the Window Manager and Location Manager, databases, telephony, and sensors.

- A user interface framework used to host and launch applications.

- A set of core preinstalled applications.

- A software development kit (SDK) used to create applications, including the related tools, IDE, sample code, and documentation.

What really makes Android compelling is its open philosophy, which ensures that you can fix any deficiencies in user interface or native application design by writing an extension or replacement. Android provides you, as a developer, with the opportunity to create applications designed to look, feel, and function exactly as you imagine them.

With more than 2 billion monthly active users of devices running the Android operating system, installing over 82 billion apps and games in from Google Play in 2016 alone, the Android ecosystem represents an unparalleled chance to create apps that can affect and improve billions of people’s lives.

PRE-INSTALLED ANDROID APPLICATIONS

Android devices typically come with a suite of preinstalled applications that users expect. On smart phones these typically include:

- A phone dialer

- An SMS management application

- A web browser

- An e-mail client

- A calendar

- A contacts list

- A music player and picture gallery

- A camera and video recording application

- A calculator

- A home screen

- An alarm clock

In many cases Android devices also ship with the following proprietary Google mobile applications:

- The Google Play Store for downloading third-party Android applications

- The Google Maps application, including StreetView, driving directions, and turn-by-turn navigation, satellite views, and traffic conditions

- The Gmail email client

- The YouTube video player

- The Google Chrome browser

- The Google home screen and Google Assistant

The data stored and used by many of these native applications—such as contact details—are also available to third-party applications.

The exact makeup of the applications available on new Android devices is likely to vary based on the hardware manufacturer, the carrier or distributor, and the type of device.

The open source nature of Android means that carriers and OEMs can customize the user interface and the applications bundled with each Android device.

It’s important to note that for compatible devices, the underlying platform and SDK remains consistent across OEM and carrier variations. The look and feel of the user interface may vary, but your applications will function in the same way across all compatible Android devices.

ANDROID SDK FEATURES

For us developers, the true appeal of Android lies in its APIs.

As an application-neutral platform, Android gives you the opportunity to create applications that are as much a part of the phone as anything provided out-of-the-box. The following list highlights some of the most noteworthy Android features:

- Transparent access to telephony and Internet resources through GSM, EDGE, 3G, 4G, LTE, and Wi-Fi network support, enabling your app to send and retrieve data across mobile and Wi-Fi networks

- Comprehensive APIs for location-based services such as GPS and network-based location detection

- Full support for integrating maps within the user interface

- Full multimedia hardware control, including playback and recording with the camera and microphone

- Media libraries for playing and recording a variety of audio/video or still-image formats

- APIs for using sensor hardware, including accelerometers, compasses, barometers, and fingerprint sensors

- Libraries for using Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and NFC hardware

- Shared data stores and APIs for contacts, calendar, and multi-media

- Background services and an advanced notification system

- An integrated web browser

- Mobile-optimized, hardware-accelerated graphics, including a path-based 2D graphics library and support for 3D graphics using OpenGL ES 2.0

- Localization through a dynamic resource framework

WHAT DOES ANDROID RUN ON?

The first Android mobile handset, the T-Mobile G1, was released in the United States in October 2008. By the end of 2017 there are more than 2 billion monthly active Android devices globally, making it the most common smart phone operating system in use world-wide.

Rather than being a mobile OS created for a single hardware implementation, Android is designed to support a large variety of hardware platforms, from smart phones to tablets, televisions, watches, and IoT devices.

With no licensing fees or proprietary software, the cost to handset manufacturers for providing Android devices is comparatively low, which, combined with a massive ecosystem of powerful applications, has encouraged device manufacturers to produce increasingly diverse and tailored hardware.

As a result, hundreds of manufacturers, including Samsung, LG, HTC, and Motorola, are creating Android devices. These devices are distributed to users via hundreds of carriers world-wide.

WHY DEVELOP FOR MOBILE?

Smart phones have become so advanced and personal to us that for many people they’ve become an extension of themselves. Studies have shown that many mobile phone users become anxious if they misplace their device, lose connectivity, or their battery runs out.

The ubiquity of mobile phones, and our attachment to them, makes them a fundamentally different platform for development from PCs. With a microphone, camera, touchscreen, location detection, and environmental sensors, a phone can effectively become an extra-sensory perception device.

Smart phone ownership easily surpasses computer ownership in many countries, with more than 3 billion mobile phone users worldwide. 2009 marked the year that more people accessed the Internet for the first time from a mobile phone rather than a PC.

The increasing popularity of smart phones, combined with the increasing availability of high-speed mobile data and Wi-Fi hotspots, has created a huge opportunity for advanced mobile applications.

Smartphone applications have changed the way people use their phones. This gives you, the application developer, a unique opportunity to create dynamic, compelling new applications that become a vital part of people’s lives.

WHY DEVELOP FOR ANDROID?

In addition to providing access to the largest ecosystem of smart phone users, Android represents a dynamic framework for app development based on the reality of modern mobile devices designed by developers, for developers.

With a simple, powerful, and open SDK, no licensing fees, excellent documentation, a diverse range of devices and form-factors, and a thriving developer community, Android represents an opportunity to create software that can change people’s lives.

The barrier to entry for new Android developers is minimal:

- No certification is required to become an Android developer.

- The Google Play Store provides free, up-front purchase, in-app billing, and subscription options for distribution and monetization of your applications.

- There is no approval process for application distribution.

- Developers have total control over their brands.

From a commercial perspective, Android represents the most common smart phone operating system, and provides access to over 2 billion monthly active Android devices globally, offering unparalleled reach to make your applications available to users around the world.

INTRODUCING THE DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK

Android applications normally are written using the Java or Kotlin programming languages, and are executed by means of the Android Run Time (ART).

Each Android application runs in a separate process, relinquishing all responsibility for memory and process management to the Android Run Time, which stops and kills processes as necessary to manage resources.

ART sits on top of a Linux kernel that handles low-level hardware interaction, including drivers and memory management, while a set of APIs provides access to all the underlying services, features, and hardware.

What Comes in the Box

The Android SDK includes everything you need to start developing, testing, and debugging Android applications:

- The Android API Libraries —The core of the SDK is the Android API libraries that provide developer access to the Android stack. These are the same libraries that Google uses to create native Android applications.

- Development tools —The SDK includes the Android Studio IDE and several other development tools that let you compile and debug your applications to turn Android source code into executable applications. You learn more about the developer tools in Chapter 2 , “Getting Started.”

- The Android Virtual Device Manager and Emulator —The Android Emulator is a fully interactive mobile device emulator featuring several alternative skins. The Emulator runs within an Android Virtual Device (AVD) that simulates a device hardware configuration. Using the Emulator you can see how your applications will look and behave on a real Android device. All Android applications run within ART, so the software emulator is an excellent development environment—in fact, because it’s hardware-neutral, it provides a better independent test environment than any single hardware implementation.

- Full documentation —The SDK includes extensive code-level reference information detailing exactly what’s included in each package and class and how to use them. In addition to the code documentation, Android’s reference documentation and developer guides explain how to get started, give detailed explanations of the fundamentals behind Android development, highlight best practices, and provide deep-dives into framework topics.

- Sample code —The Android SDK includes a selection of sample applications that demonstrate some of the possibilities available with Android, as well as simple programs that highlight how to use individual API features.

-

Online support

—Android has vibrant developer communities on most online social networks, Slack, and many developer forums. Stack Overflow (

www.stackoverflow.com/questions/tagged/android) is a hugely popular destination for Android questions and a great place to find answers to beginner questions. Many Android engineers from Google are active on Stack Overflow and Twitter.

Understanding the Android Software Stack

The Android software stack is a Linux kernel and a collection of C/C++ libraries exposed through an application framework that provides services for, and management of, the run time and applications, as shown in Figure 1-1 .

- Linux kernel —Core services (including hardware drivers, process and memory management, security, network, and power management) are handled by a Linux kernel (the specific kernel version depends on the Android platform version and hardware platform).

- Hardware Application Layer (HAL) —The HAL provides an abstraction layer between the underlying physical device hardware and the remainder of the stack.

-

Libraries

—Running on top of the kernel and HAL, Android includes various C/C++ core libraries such as libc and SSL, as well as the following:

- A media library for playback of audio and video media

- A surface manager to provide display management

- Graphics libraries that include SGL and OpenGL for 2D and 3D graphics

- SQLite for native database support

- SSL and WebKit for integrated web browser and Internet security

- Android Run Time —The run time is what makes an Android phone an Android phone rather than a mobile Linux implementation. Including the core libraries, the Android Run Time is the engine that powers your applications and forms the basis for the application framework.

- Core libraries —Although most Android application development is written using the Java or Kotlin JVM languages, ART is not a Java VM. The core Android libraries provide most of the functionality available in the core Java libraries, as well as the Android-specific libraries.

- Application framework —The application framework provides the classes used to create Android applications. It also provides a generic abstraction for hardware access and manages the user interface and application resources.

- Application layer —All applications, both native and third-party, are built on the application layer by means of the same API libraries. The application layer runs within the Android Run Time, using the classes and services made available from the application framework.

The Android Run Time

One of the key elements of Android is the Android Run Time (ART). Rather than using a traditional Java VM such as Java ME, Android uses its own custom run time designed to ensure that multiple instances run efficiently on a single device.

ART uses the device’s underlying Linux kernel to handle low-level functionality, including security, threading, and process and memory management. It’s also possible to write C/C++ applications that run closer to the underlying Linux OS. Although you can do this, in most cases there’s no reason you should need to.

If the speed and efficiency of C/C++ is required for your application, Android provides a native development kit (NDK). The NDK is designed to enable you to create C++ libraries using the libc and libm libraries, along with native access to OpenGL.

All Android hardware and system service access is managed using ART as a middle tier. By using this run time to host application execution, developers have an abstraction layer that ensures they should never have to worry about a particular hardware implementation.

ART executes Dalvik executable files (

.dex

)—named after an earlier virtual machine implementation named “Dalvik”—a format optimized to ensure minimal memory footprint. You create

.dex

executables by transforming Java or Kotlin language compiled classes using the tools supplied within the SDK.

Android Application Architecture

Android’s architecture encourages component reuse, enabling you to publish and share Activities, Services, and data with other applications, with access managed by the security restrictions you define.

The same mechanism that enables you to produce a replacement contact manager or phone dialer can let you expose your application’s components in order to let other developers build on them by creating new UI front ends or functionality extensions.

The following application services are the architectural cornerstones of all Android applications, providing the framework you’ll be using for your own software:

- Activity Manager and Fragment Manager —Activities and Fragments are used to define the user interface of your apps. The Activity and Fragment Managers control the life cycle of your Activities and Fragments, respectively, including management of the Activity stack (described in Chapters 3 and 5 ).

- Views —Used to construct the user interfaces controls within your Activities and Fragments, as described in Chapter 5 .

- Notification Manager —Provides a consistent and nonintrusive mechanism for signaling your users, as described in Chapter 11 .

- Content Providers —Lets your applications share data, as described in Chapter 10 .

- Resource Manager —Enables non-code resources, such as strings and graphics, to be externalized, as shown in Chapter 4 .

- Intents —Provides a mechanism for transferring data between applications and their components, as described in Chapter 6 .

Android Libraries

Android offers a number of APIs for developing your applications. Rather than list them all here, check out the documentation at

developer.android.com/reference/packages.html

, which gives a complete list of packages included in the Android SDK.

Android is intended to target a wide range of mobile hardware, so be aware that the suitability and implementation of some of the advanced or optional APIs may vary depending on the host device.

2

Getting Started

GETTING STARTED DEVELOPING ANDROID APPS

All you need to start writing your own Android applications is a copy of the Android SDK and a Java Development Kit (JDK). Unless you’re a masochist, you’ll also want to use an integrated development environment (IDE)—we strongly recommend using Android Studio, Google’s officially supported IDE for Android app development that includes an integrated JDK and manages the installation of the Android SDK and associated tools.

Android Studio, the Android SDK, and a JDK are each available for Windows, MacOS, and Linux, so you can explore Android from the comfort of whatever operating system (OS) you favor. Android applications themselves are run within the ART managed runtime, optimized for resource-constrained mobile devices, so there’s no advantage to developing on any particular OS.

Traditionally, Android code is written using Java language syntax—until 2017 Android app development required the use of Java. Android Studio 3.0 added Kotlin as a fully supported language alternative, allowing you to write Android app in part, or entirely, using Kotlin.

Kotlin is a statically typed language that is fully interoperable with Java source files and the Android runtime. It’s considered expressive and concise and introduces improvements including reduced language verbosity, null-pointer safety, extension functions, and infix notation.

The core Android libraries include most of the features from the core Java APIs in addition to the rich suite of Android-specific APIs. You can access all these libraries using either Java or Kotlin when writing your apps.

Although it’s possible to download and install the Android SDK and JDK separately, installing and using Android Studio simplifies the process of getting started. Android Studio includes an integrated OpenJDK and manages the installation of the Android SDK components and tools using the integrated Android SDK Manager.

The SDK Manager is used to download Android framework SDK libraries and optional add-ons (including the Google APIs and support libraries). It also includes the platform and development tools you will use to write and debug your applications, such as the Android Emulator to run your projects and the Android Profiler to profile CPU, memory, and network use. All these tools are integrated directly into Android Studio for your convenience.

By the end of this chapter, you’ll have installed Android Studio, the Android SDK and its add-ons, and the development tools. You’ll have set up your development environment, built your first Hello World application in Java and Kotlin, and run and debugged it using the DDMS and Emulator running on an Android Virtual Device (AVD).

If you’ve developed for mobile devices before, you already know that their small form factor, limited battery life, and restricted processing power and memory create some unique design challenges. Even if you’re new to the game, it’s obvious that some of the things you can take for granted on the desktop, web, or server—such as always-on Internet and power—aren’t applicable when writing apps for mobile or embedded devices.

The user environment brings its own challenges in addition to those introduced by hardware limitations. Many Android devices are used on the move and are often a distraction rather than the focus of attention, so your application needs to be fast, responsive, and easy to learn. Even if your application is designed for devices more conducive to an immersive experience, such as tablets or televisions, the same design principles can be critical for delivering a high-quality user experience.

DEVELOPING FOR ANDROID

The Android SDK includes all the tools and APIs you need to write compelling and powerful mobile applications. The biggest challenge with Android, as with any new development toolkit, is learning the features and limitations of those APIs.

Since Android Studio 3.0, it’s possible to write Android apps using Java, Kotlin, or a combination of both languages. If you have experience in Java or Kotlin development, you’ll find that the syntax and grammar you’ve been using will translate directly into Android. If you don’t have experience with Java, but have used other object-oriented languages (such as C#), you should find the transition to either Java or Kotlin syntax straightforward.

The power of Android comes from its APIs, not the language being used, so being unfamiliar with Java or Kotlin syntax and/or Java-specific classes won’t present a meaningful disadvantage.

There’s no cost to download or use the SDK, and Google doesn’t require your application to pass a review to distribute your finished apps on the Google Play Store. Although Google Play requires a small one-time fee to publish applications, if you choose not to distribute via the Google Play Store, you can do so at no cost.

What You Need to Begin

Because Android applications run within the Android Run Time, you can write them on any platform that supports the developer tools. Throughout this book we’ll be using Android Studio, which currently supports:

- Microsoft Windows 7/8/10 (32- or 64-bit)

- Mac OS X 10.8.5 or later

- GNOME or KDE Linux desktop (including GNU C Library 2.11 or later)

On all platforms, Android Studio requires at least 2 GB of RAM (with 8 GB strongly recommended), and 1280 x 800 minimum screen resolution.

Developing with Android Studio

The examples and step-by-step instructions in this book are targeted at developers using Android Studio. Android Studio is Android’s official IDE, built on top of IntelliJ IDEA, a popular IDE for Java development that also supports Android development using Kotlin.

Android Studio is purpose-built by the Android team at Google to accelerate your development and help you build high-quality apps. It supports all Android form factors including phones, tablets, TV, Wear, and Auto—and offers tools tailored specifically for Android developers, including rich code editing, debugging, testing, and profiling.

Some of Android Studio’s features include:

- Intelligent code editing with advanced code completion, refactoring, and code analysis.

- Version control integration including GitHub and Subversion.

- Robust static analysis framework with over 280 different Lint checks along with quick fixes.

- Extensive testing tools and frameworks including JUnit 4 and functional UI tests. You can run your tests on a device, an emulator, a continuous integration environment, or in the Firebase Test Lab.

In addition to these IDE features, using Android Studio for your Android development offers some significant advantages through the tight integration of many of the Android build and debug tools, as well as ensured support for the latest Android platform releases.

Android Studio includes the following features:

- The Android Project Wizard, which simplifies creating new projects and includes several application and Activity templates

- Editors to help create, edit, and validate your XML resources

-

Automated building of Android projects, conversion to Android executables (

.dex), packaging to package files (.apk), and installation of packages onto Android Run Times (running both within the Emulator or on physical devices) - The Android Virtual Device manager, which lets you create and manage virtual devices to host Emulators that run a specific release of the Android OS and with set hardware and memory constraints

- The Android Emulator, including the ability to control the Emulator’s appearance and network connection settings, and the ability to simulate incoming calls, SMS messages, and sensor values

- The Android Profiler, which lets you monitor CPU, memory, and network performance

- Access to the device or Emulator’s filesystem, enabling you to navigate the folder tree and transfer files

- Runtime debugging, which enables you to set breakpoints and view call stacks

- All Android logging and console outputs

Installing Android Studio and the Android SDK

You can download the latest version of Android Studio for your chosen development platform from the Android Studio homepage at

developer.android.com/studio

.

When you have initiated the download for your platform, you will be shown detailed installation instructions that can be summarized as follows:

- Windows —Run the downloaded installation executable. The Windows installer download includes OpenJDK and the Android SDK.

-

MacOS

—Open the downloaded Android Studio

DMGfile, and then drag Android Studio into your “Applications”folder. Double-click to open Android Studio, and the Setup Wizard will guide you through the rest of the setup, which includes downloading the Android SDK. -

Linux

—Unzip the downloaded

.zipfile to an appropriate location for your applications, such as within/usr/local/for your user profile, or/opt/for shared users. Open a terminal, navigate to theandroid-studio/bin/directory, and executestudio.sh. The Setup Wizard will then guide you through the rest of the setup, which includes downloading the Android SDK.

Since Android Studio 2.2, OpenJDK has been integrated with Android Studio, ensuring you don’t need to download and install the JDK separately.

Once the installation wizard is completed, the latest Android platform SDK; SDK, platform, and build tools; and support library will have been downloaded and installed.

You can download older platform versions, as well as additional SDK components using the SDK Manager as described in the following section.

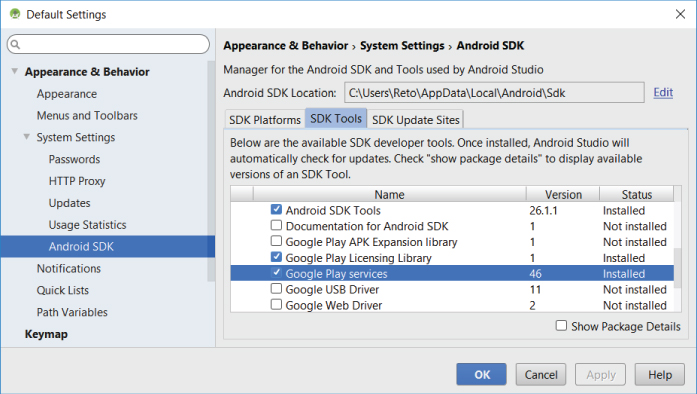

Installing Additional Android SDK Components Using the SDK Manager

The SDK Manager (

Figure 2-1

) is available through a shortcut on the toolbar, the Android SDK settings option, or from within the Tools

Android

Android

SDK Manager menu item. It offers tabs for SDK Platforms, SDK Tools, and SDK Update Sites.

SDK Manager menu item. It offers tabs for SDK Platforms, SDK Tools, and SDK Update Sites.

The SDK Platforms tab shows which platform SDKs you have downloaded. By default, this will include the newest Android platform SDK—in this case, Android 8.1 Oreo (API Level 27).

The SDK Tools tab shows which tools and support libraries you have installed, including the SDK, platform, and build tools—as well as the support repository, which is required to use the Android Support Library (described later in this chapter.)

By selecting the Show Package Contents Details checkbox, you can find additional details on which versions each tool have been installed.

Downloading and Installing Updates to Android Studio, the Android SDK, and Tools

Android Studio receives frequent updates that improve stability and add new features. You will be prompted with an alert tip when a new version of Android Studio is available for download, as shown in Figure 2-2 .

You will similarly be prompted when new revisions of the Android SDK, developer tools, support library, Kotlin, and other SDK packages become available.

You can force a check for a new version of Android Studio by opening the Settings dialog box and navigating to Settings

Updates and clicking the “Check Now” button, as shown in

Figure 2-3

, or by selecting the Help

Updates and clicking the “Check Now” button, as shown in

Figure 2-3

, or by selecting the Help

Check For Updates menu item.

Check For Updates menu item.

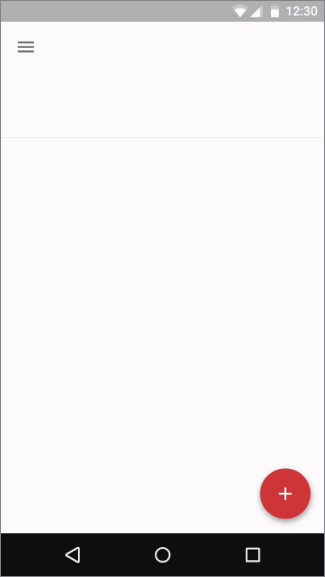

Creating Your First Android Application

With Android Studio installed and the SDK downloaded you’re ready to start developing apps for Android. You’ll begin by creating a new Android project, configuring the Android Emulator, and setting up your Android Studio run and debug configurations, as described in the following sections.

Creating a New Android Project

To create a new Android project using Android Studio’s New Project Wizard, do the following:

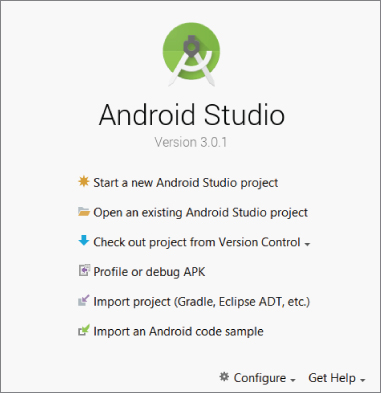

-

The first time you start Android Studio you are presented with the welcome screen shown in

Figure 2-4

. You can return to this screen by selecting the File

Close menu item to close any open projects. From the welcome screen, select the “Start a new Android Studio project” option. Alternatively, within Android Studio select the File

Close menu item to close any open projects. From the welcome screen, select the “Start a new Android Studio project” option. Alternatively, within Android Studio select the File

New

New

New Project… menu item.

New Project… menu item.

-

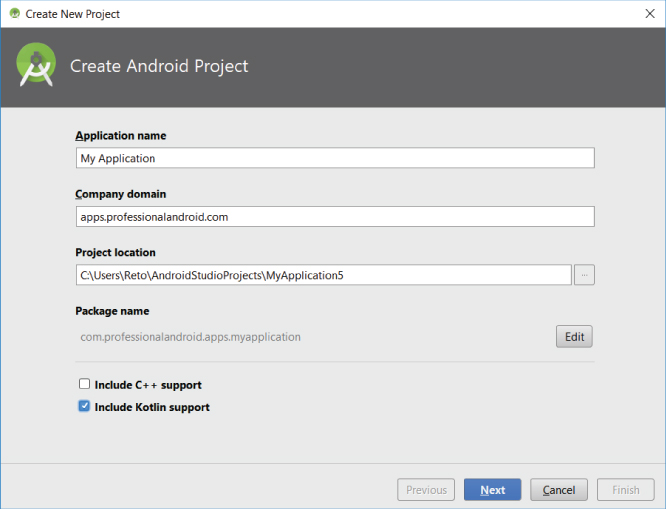

In the wizard that appears, enter the details for your new project. On the first page (

Figure 2-5

) enter an Application Name and your Company Domain. These will be combined to create a unique Package Name as displayed on the wizard.

Each Android application must have a unique package name, so it’s good practice to use a domain you own to minimize the chance of a collision. That said, owning the domain you use isn’t required or enforced, so you can use almost any domain you want provided the resulting package name is unique.

Finally, select the directory location to which your project will be saved.

-

The next page (

Figure 2-6

) lets you select the form factors you wish to support within this project, as well as the minimum Android platform version on which your application will run. To get started, we’ll target just phones and tablets and use the default minimum SDK.

-

The next page (

Figure 2-7

) lets you select a template for your app’s main Activity (user interface screen). Select the Empty Activity.

-

The final page (

Figure 2-8

) allows you to specify the class name for your initial Activity, and specify the name for the XML file that will be used to provide the Activity’s UI layout. In the case of the empty Activity template, you can also choose if you wish the wizard to generate a layout file at all. You also have the option to make your Activity backward compatible by selecting the Backwards Compatibility check box, which is highly recommended. Marking this box checked will result in the new Activity inheriting from the Android Support Library’s

AppCompatActivityclass rather than the framework’sActivityclass, which will allow your Activity to take advantage of new API features in a way that’s backward compatible.

- When you’ve entered these details, click Finish.

Android Studio will now create a new project that includes a class that extends

AppCompatActivity

. Rather than being completely empty, the default template implements “Hello World.”

Before modifying the project, take this opportunity to create an Android Virtual Device, enable debugging on a physical device, and run our new Hello World project.

Creating an Android Virtual Device

Android Virtual Devices (AVDs) are used to simulate the hardware and software configurations of physical Android devices. The Android Emulator runs within AVDs, allowing you test your applications on a variety of different hardware and software platforms.

There are no prebuilt AVDs included in the Android Studio or Android SDK downloads so, if you don’t have a physical device, you’ll need to create at least one before you can run and debug your applications:

-

Select Tools

Android

Android

AVD Manager (or select the AVD Manager icon on the Android Studio toolbar).

AVD Manager (or select the AVD Manager icon on the Android Studio toolbar).

-

Click the “Create Virtual Device…” button.

The resulting Virtual Device Configuration dialog box ( Figure 2-9 ) allows you to select a device definition from a list of Pixel and Nexus hardware and standard device configurations—each with its own physical size, resolution, and pixel density.

-

You’ll then be asked to select a device system image corresponding to a particular Android platform release, as shown in

Figure 2-10

. If you have not already done so, you will need to download the desired system image before it can be used.

Notice that for each platform release you can choose system images for different ABIs (application binary interfaces)—typically x86 or ARM. Consider using a system image using the same architecture as your host computer to maximize Emulator performance.

You can also decide if you want a system image that includes the Google APIs. These are necessary if your app includes Google Play Services features such as maps and Location Based Services, as described in Chapter 15 .

-

Specify a descriptive device name, and then hit Finish to create a new AVD, as shown in

Figure 2-11

. Note that by clicking Show Advanced Settings you can reveal additional options to assign your webcam to the front or rear camera, adjust the emulated network speed and latency, and customize the number of emulated cores, system memory, and storage.

- Starting a new AVD can take some time, so start it now by clicking the green arrow in the right-most column. This will ensure the emulator is prepared and running when you’re ready to run your app on it.

Configuring a Physical Device for Testing and Debugging

There’s nothing quite like making software run on real hardware, so if you have an Android device, it’s simple to run and debug your applications on it directly:

-

Start by enabling developer mode on your device. Open the phone’s Settings and find and select System

“About phone.” Scroll to the bottom of the resulting list until “Build number” is visible, as shown in

Figure 2-12

.

“About phone.” Scroll to the bottom of the resulting list until “Build number” is visible, as shown in

Figure 2-12

.

- Touch “Build number” seven times, until a message is displayed congratulating you on becoming a developer. If you embarked on your journey to become an Android developer to win a bet, you can now safely collect. Congratulations!

-

If not, navigate back, and you’ll find a new settings category labeled “Developer options.” Select it, and scroll until you see the option for “USB debugging,” as shown in

Figure 2-13

.

- Enable “USB debugging.”

-

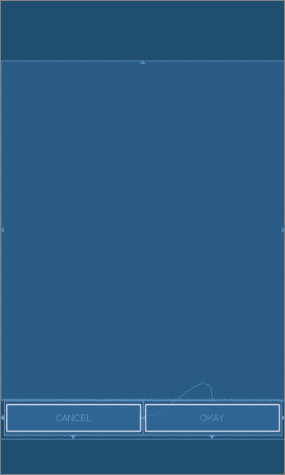

Now connect your device to your development host computer using a USB cable. Your device will display the dialog box shown in

Figure 2-14

, asking if you wish to allow USB debugging when connected to the current computer. Select OK.

- When connected, this device will now be available as a target when launching your app for running or debugging within Android Studio.

Running and Debugging Your Android Application

You’ve created your first project and created an Android Virtual Device (or connected a physical device) on which to run it. Before making any changes, let’s try running and debugging the Hello World project.

From the Run menu, select “Run app” (or “Debug app”). If you haven’t already selected a default, you’ll be presented with the dialog box shown in Figure 2-15 , asking you to select your deployment target—a connected device, a running AVD, or a defined (but not yet running) AVD.

Running or debugging your application does the following behind the scenes:

-

Compiles the current project source to bytecode, and converts that to an Android executable (

.dex) -

Packages the executable and your project’s resources and manifest into an Android package (

.apk) - Starts the virtual device (if you’ve targeted one and it’s not already running)

- Deploys your APK to the target device and installs it

- Starts your application

If you’re debugging, the Android Studio debugger will then be attached, allowing you to set breakpoints and debug your code.

If everything is working correctly, you’ll see a new Activity running on the device or in the Emulator, as shown in Figure 2-16 .

Understanding Hello World

Take a step back and have a look at the source code for your first Android application, starting with the

MainActivity.java

file.

In Android,

Activity

is the base class for the visual, interactive screens within your application; it is roughly equivalent to a Form in traditional desktop development (and is described in detail in

Chapter 3

, “Applications and Activities and Fragments, Oh My!”).

AppCompatActivity

is a variation of the

Activity

class supplied by the Android Support Library, which provides backward compatibility. Using

AppCompatActivity

in preference to the

Activity

class is considered best practice, and we’ll be doing so throughout this book. Note that by convention we still refer to classes that extend

AppCompatActivity

as

Activities

.

Listing 2-1

shows the skeleton code for an Activity; note that it extends

AppCompatActivity

and overrides the

onCreate

method.

Visual components within Activities are called

Views

, which are similar to controls or widgets in traditional desktop and web development. The Hello World template created by the wizard overrides

the

onCreate

method to call

setContentView

, which lays out the UI by inflating a layout resource, as highlighted in bold in the following snippet:

@Overrideprotected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);setContentView(R.layout.activity_main);}

The resources for an Android project are stored in the

res

folder of your project hierarchy, which includes

layout

,

values

,

drawable

, and

mipmap

subfolders. Android Studio interprets these resources and provides design-time access to them through the

R

variable, as described in

Chapter 4

.

Listing 2-2

shows the UI layout as defined in the

activity_main.xml

file, created by the Android project template and stored in the project’s

res/layout

folder.

Defining your UI in XML and inflating it is the preferred way of implementing your user interfaces (UIs), because it neatly decouples your application logic from your UI design.

To get access to your UI elements in code, you can add identifier attributes to them in the XML definition:

<TextViewandroid:id="@+id/myTextView"android:layout_width="wrap_content"android:layout_height="wrap_content"android:text="Hello World!"app:layout_constraintBottom_toBottomOf="parent"app:layout_constraintLeft_toLeftOf="parent"app:layout_constraintRight_toRightOf="parent"app:layout_constraintTop_toTopOf="parent"/>

You can then use the

findViewById

method to return a reference to each named item at run time:

TextView myTextView = findViewById(R.id.myTextView);

Alternatively (although it’s not generally considered good practice), you can create your layout directly in code, as shown in Listing 2-3 .

Note that all the properties available in code can also be set with attributes in the XML layout.

More generally, keeping the visual design decoupled from the application code helps keep the code concise. With Android available on hundreds of different devices of varying screen sizes, defining your layouts as XML resources makes it easier for you to include multiple layouts optimized for different screens.

You learn how to build your user interface by creating layouts and building your own custom Views in Chapter 5 , “Building User Interfaces.”

Opening Android Sample Projects

Android includes a number of well-documented sample projects that are an excellent source for full, working examples of applications written for Android. When you finish setting up your development environment, it’s worth going through some of them.

The Android sample projects are stored on GitHub, and Android Studio provides a simple mechanism for cloning them:

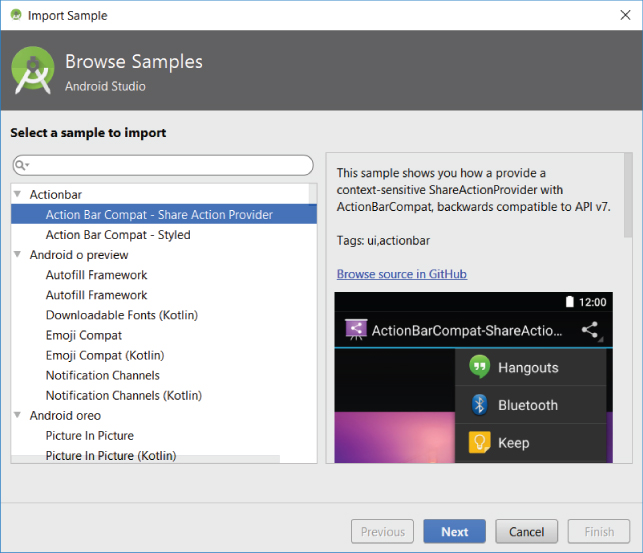

-

From within Android Studio, select File

New

New

Import Sample… to open the Import Sample Wizard, as shown in

Figure 2-17

. You can also select “Import an Android code sample” from the Welcome to Android Studio Wizard if you have no projects currently open.

Import Sample… to open the Import Sample Wizard, as shown in

Figure 2-17

. You can also select “Import an Android code sample” from the Welcome to Android Studio Wizard if you have no projects currently open.

- Select the sample you wish to import and click Next.

- Specify an application name and location on your host machine and click Finish to download and open the sample.

The selected sample project will be cloned from GitHub and be opened as a new Android Studio project.

Getting Started Writing Android Apps Using Kotlin

Until 2017, Android app development required the use of the Java language syntax. Android Studio 3.0 added Kotlin as a fully supported language alternative.

Kotlin is a statically typed language that is fully interoperable with the existing Java language syntax and runtime used with Android. It’s considered expressive and concise, and introduces improvements including reduced language verbosity, null-pointer safety, extension functions, and infix notation.

Since Android Studio 3.0, Kotlin is an officially supported Android development language; however, at the time of this book’s writing, Java was still the default for new projects—and most existing Android projects were still written predominantly using Java syntax. It’s also very easy to convert Java syntax into Kotlin, simply by pasting Java syntax into a Kotlin source file. As a result, we have used Java syntax within the code snippets and sample projects featured within this book.

Given the advantages of Kotlin in terms of improved development time and code readability, we expect the proportion of apps written primarily in Kotlin to increase quickly, and we highly recommend that you familiarize yourself with the Kotlin language for writing Android apps. To assist, each of the code snippets and sample projects are also available in Kotlin, downloadable from the Wrox site alongside the Java syntax versions.

Your Android projects can be written from scratch in Kotlin, can include interoperable Kotlin and Java source files, or can be converted from Java source files to Kotlin during development.

To begin a new project in Kotlin, select the File

New

New

New Project… menu item, as previously described, but on the first page of the wizard, select the “Include Kotlin support” checkbox, as shown in

Figure 2-18

.

New Project… menu item, as previously described, but on the first page of the wizard, select the “Include Kotlin support” checkbox, as shown in

Figure 2-18

.

Proceed through the wizard as described in the earlier section. When complete, take a look at the Kotlin source code for your Activity in the

MainActivity.kt

file. Kotlin files are stored alongside Java source files and can be found in the Java folder when using the Android project view:

package com.professionalandroid.apps.myapplicationimport android.support.v7.app.AppCompatActivityimport android.os.Bundleclass MainActivity : AppCompatActivity() {override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)setContentView(R.layout.activity_main)}}

Note that while the code is somewhat more concise, the syntactic changes at this point are minimal. The package and import statements are the same, the

MainActivity

class still extends

AppCompatActivity

, and the override of the

onCreate

method remains the same.

To add a new Kotlin file to your project, select Kotlin from the Source Language dropdown list when adding a new application component from the File

New menu. Alternatively, you can select the File

New menu. Alternatively, you can select the File

New

New

Kotlin File/Class menu item to create a basic file.

Kotlin File/Class menu item to create a basic file.

Because Kotlin and Java files can coexist in the same project, it’s possible to add Kotlin source files to a project you started without ticking the Kotlin support checkbox or to add Java source files to a project started with Kotlin support.

It’s also possible to convert existing Java syntax source files into Kotlin. You can do this by opening an existing Java source file and selecting the Code

Convert Java File to Kotlin File menu item. Alternatively, you can create a new Kotlin file and paste Java syntax source code into it. You will be prompted to convert the pasted code into Kotlin, as shown in

Figure 2-19

.

Convert Java File to Kotlin File menu item. Alternatively, you can create a new Kotlin file and paste Java syntax source code into it. You will be prompted to convert the pasted code into Kotlin, as shown in

Figure 2-19

.

Note that these automatic conversions may not always use idiomatic Kotlin, so the resulting code might not use Kotlin’s best language features.

Using the Android Support Library Package

The Android Support Library package (also referred to as the compatibility library or AppCompat) is a set of libraries you can include as part of your projects, to gain either convenience APIs that aren’t packaged as part of the framework (such as the View Pager), or useful APIs that are not available on all platform releases (such as Fragments).

The Support Library enables you to use framework API features that were introduced in newer Android platform releases on devices running earlier platform versions. This helps you provide a consistent user experience and greatly simplifies your development process by reducing the burden of supporting older platform versions, while taking advantage of newer features.

The Android Support Library package contains several individual libraries, each of which offers support for a specific range of Android platform versions and features.

We will introduce new libraries as required in the following chapters. To begin with, it’s good practice to include the v7 appcompat library in all new projects because it supports a wide range of Android versions—back to Android 2.3 Gingerbread (API Level 9)—and provides APIs for many recommended user interface patterns.

The application templates provided by Android Studio—including the Hello World example we created earlier—include a dependency on the v7 appcompat library by default.

To incorporate an Android Support Library package into your project, perform the following steps:

- Use the SDK Manager to ensure you have downloaded the Android Support Repository.

-

Add a dependency to your Gradle build for the desired library, either by:

-

2.1 Opening your

module:app build.gradlefile and adding a reference to the library name and version you wish to include, within the dependency node:dependencies {[… Existing dependencies …]implementation 'com.android.support:appcompat-v7:27.1.1'} -

2.2 Or using Android Studio’s Project Structure UI, as shown in

Figure 2-20

. Select the File

Project Structure…, menu item and then select your app module from the list on the left before choosing the Dependencies tab. Add a new library by selecting the green “plus” symbol on the right-side toolbar and selecting the desired library.

Project Structure…, menu item and then select your app module from the list on the left before choosing the Dependencies tab. Add a new library by selecting the green “plus” symbol on the right-side toolbar and selecting the desired library.

-

2.1 Opening your

Notice that we’re adding a dependency to a specific version of the support library. By design, the Android Support Library package will be updated more regularly than the Android framework SDK. By downloading new versions of the Support Libraries, and updating your dependencies to reference the newest releases, you can continue to incorporate bug fixes and improvements to your app as the Support Libraries are updated.

DEVELOPING FOR MOBILE AND EMBEDDED DEVICES

Android does a lot to simplify mobile- or embedded-device software development, but to build high-quality apps you need to understand the reasons behind the conventions. You have several factors to consider when writing software for mobile and embedded devices, and when developing for Android in particular.

Hardware-Imposed Design Considerations

Small and portable, mobile devices offer exciting opportunities for software development. Their limited screen size and reduced memory, storage, and processor power are far less exciting, and instead present some unique challenges.

Compared to desktop or notebook computers, mobile devices have relatively:

- Low processing power

- Limited RAM

- Limited storage capacity

- Small screens

- High costs associated with data transfers

- Intermittent connectivity, slow data transfer rates, and high latency

- Limited battery life

Each new generation of devices improves on many of these restrictions, but the device ecosystem also caters for a wide variety of prices—which results in significant variety in hardware capabilities. This is amplified by the huge growth in smart phone adoption in emerging markets, which are significantly more price sensitive, and that in turn results in large numbers of new devices with lower specification hardware.

The expansion of Android into an increasingly diverse variety of form factors—including tablets, TVs, automotive head-units, and wearable devices further expands the range of devices on which your application may be running.

In some cases you may find your app running on hardware significantly more powerful than you expected; however it’s always good practice to design to accommodate the worst-case scenario to ensure you’re providing a great user experience to all users, no matter what their hardware platform.

Performance Matters

Manufacturers of embedded devices, particularly mobile devices, often value thinner form factors and bigger (and higher resolution) screens over significant improvements to processor speeds. For us as developers, that means losing the head start traditionally afforded thanks to Moore’s law (the doubling of the number of transistors placed on an integrated circuit every two years). In desktop and server hardware, Moore’s Law typically results directly in processor performance improvements; for mobile devices, it instead means thinner devices, with brighter, higher-resolution screens. By comparison, improvements in processor power take a back seat.

In practice, this means that you always need to optimize your code so that it runs quickly and responsively, assuming that hardware improvements over the lifetime of your software are unlikely to do you any favors.

Code efficiency is a big topic in software engineering, so I’m not going to try to cover it extensively here. Later in this chapter you learn some Android-specific efficiency tips, but for now note that efficiency is particularly important for resource-constrained platforms.

Expect Limited Storage Capacity

Advances in flash memory and solid-state disks have led to a dramatic increase in mobile-device storage capacities. Although devices with 64, 128, or even 256 GB of storage are no longer uncommon, many popular lower-end devices have significantly less available space. Given that most of the available storage on a mobile device is likely to be used to store photos, music, and movies, users are likely to uninstall apps that are taking a disproportionate amount of storage space relative to their perceived value.

As a result, the install size of your application is an important consideration, though even more important is ensuring that your application is polite in its use of system resources—so you must carefully consider how you store your application data.

To make life easier, you can use the Android databases to persist, reuse, and share large quantities of data, as described in Chapter 9 , “Creating and Using Databases.” For files, preferences, and state information, Android provides optimized frameworks, as described in Chapter 8 , “Files, Saving State, and User Preferences.”

Part of being polite is cleaning up after yourself. Techniques such as caching, pre-fetching, and lazy loading are useful for limiting repetitive network lookups and improving application responsiveness, but don’t leave files on the filesystem or records in a database when they’re no longer needed.

Design for Different Screens and Form Factors

The small size and portability of mobiles are challenge for creating good interfaces, particularly when users are demanding an increasingly striking and information-rich graphical user experience. Combined with the wide range of screen sizes that make up the Android device ecosystem, creating consistent, intuitive, and delightful user interfaces can be a significant challenge.

Write your applications knowing that users will often only glance at the screen. Make your applications intuitive and easy to use by reducing the number of controls and putting the most important information front and center.

Graphical controls, such as the ones you’ll create in Chapter 5 , are an excellent means of displaying a lot of information in a way that’s easy to understand. Rather than a screen full of text with a lot of buttons and text-entry boxes, use colors, shapes, and graphics to convey information.

You’ll also need to consider how touch input is going to affect your interface design, and how you can support accessibility and non–touch screen devices such as TVs.

Android devices are now available in a huge variety of screen sizes, resolutions, and input mechanisms. With multi-window support included in Android 7.0, the screen size for your app may even change while running on a single device.

To ensure that your application looks good and behaves well on all the possible host devices, you need to create responsive designs and test your application on a variety of screens, optimizing for small screens and tablets, while also ensuring that your UIs scale well.

You learn some techniques for optimizing your UI for different screen sizes in Chapters 4 and 5 .

Expect Low Speeds, High Latency

The ability to connect to the Internet is a big part of what has made smart phones smart, and ubiquitous. Unfortunately, mobile Internet connectivity isn’t as fast, reliable, cheap, or readily available as we would like; when you’re developing your Internet-based applications, it’s best to assume that the network connection will be slow, intermittent, expensive, and unreliable.